A tale of two fuel policies: Our obsession with Malaysia's RON95, and why Singapore's pumps will never go as low

20 Apr 2022|4,340 views

What do unnecessary car jacks, enforcement officers at petrol stations, and one ruffled ex-Prime Minister of Malaysia have in common?

Penny-pinching Singaporeans, it seems.

After more than a decade, pleading ignorance when refuelling illegally in Malaysia is no longer excusable The festivities that had kicked into full gear as the border reopened were dampened mere days after, as accounts of the aforementioned behaviour started to light the Internet up. One driver had raised his car on a hydraulic jack in what was likely an attempt to get more petrol into his tank. Multiple cars were also turned back for not having their tanks ¾ full. And then, there were the RON95 thieves.

After more than a decade, pleading ignorance when refuelling illegally in Malaysia is no longer excusable The festivities that had kicked into full gear as the border reopened were dampened mere days after, as accounts of the aforementioned behaviour started to light the Internet up. One driver had raised his car on a hydraulic jack in what was likely an attempt to get more petrol into his tank. Multiple cars were also turned back for not having their tanks ¾ full. And then, there were the RON95 thieves.

Reserved solely for the consumption of Malaysian drivers, RON95 (Research Octane Number 95, in full) has been banned from Singaporean cars since August 2010. The differences in dollars and cents may indicate why; even the most aggressive discounts applied by the most mathematically-inclined drivers will not depress one litre of 95-grade petrol below S$2.50... yet drive a few kilometres north of Woodlands, and you'll see RON95 retailing at RM2.20 per litre (that's just above S$0.70 at prevailing exchange rates).

On the surface, a full decade (and more) of enshrining this ban into law hasn't appeared sufficient in sending the message to some stubborn, errant drivers. Peeling back the issue, however, would circle us back to the innate displeasure that Singaporeans have with how petrol is priced on our shores.

All this does resurface the question of whether Singapore's pumps are overpriced - but it also begs another question we ask less frequently: Are Malaysia's pumps under-priced?

From crude oil to refined petrol: A quick explainer

The relentless fluctuation of crude oil prices has been intensely scrutinised over the last two years The volatility of crude oil prices has come under intense scrutiny over the last two years, spurred, no less, by catastrophic events whose effects have reverberated through the entire globe. But either direction things go, it seems the end result is that we're still bothered - ruffled when pump prices skyrocket (as barrel prices shoot through the roof), and indignant when prices don't seem to fall when they should.

The relentless fluctuation of crude oil prices has been intensely scrutinised over the last two years The volatility of crude oil prices has come under intense scrutiny over the last two years, spurred, no less, by catastrophic events whose effects have reverberated through the entire globe. But either direction things go, it seems the end result is that we're still bothered - ruffled when pump prices skyrocket (as barrel prices shoot through the roof), and indignant when prices don't seem to fall when they should.

After all, didn't crude oil prices plummet to sub-zero levels at one point during the pandemic? Shouldn't these fluctuations also then be passed on to us (but more of the lows, less of the highs, please)?

Yes… And no.

Undeniably, how much a barrel of crude oil costs affects the amount petrol will retail at - it's the very basic material form, after all, from which any sort of processing starts. But therein lies the catch: It needs to be refined. And refining comes with its own extra considerations.

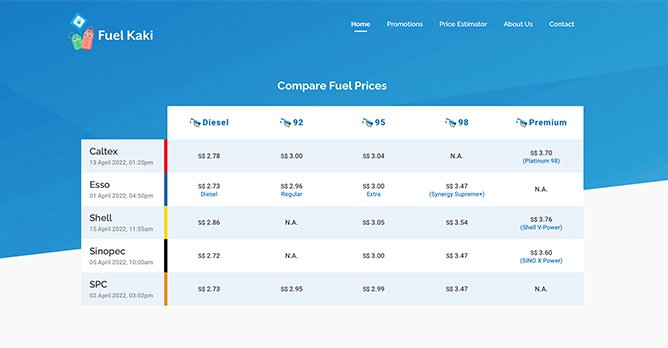

This is why operators across Asia take reference from the Mean of Platts Singapore (MOPS), a benchmark pricing calculated by an assessment agency dedicated to refined oil products. It is from hereon that operators begin to formulate the numbers that we eventually see when we pull up to a petrol station (or on Fuel Kaki and Waze).

Naturally, however, more goes into the equation. Among other costs, wages for workers as well as land (and therefore rental) costs all find their way into the eventual retail prices for petrol as well. In 2015, a local study indicated that MOPS accounted for less than a third of what we were paying for at the pumps (it's not far-fetched to consider that this hasn't changed too drastically over the years). In Malaysia - where the industry also relies on MOPS - that figure currently stands at close to 50%.

RON95: A (costly) privilege, reserved only for the rakyat

To make inflation more manageable for its citizens, especially post-pandemic, the Malaysian government continues to substantially subsidise fuel Whether petrol in Malaysia is under-priced is a question that cannot be answered definitively (and most certainly not by a Singaporean). What can be objectively stated, however, is that its pumps are heavily subsidised by the government.

To make inflation more manageable for its citizens, especially post-pandemic, the Malaysian government continues to substantially subsidise fuel Whether petrol in Malaysia is under-priced is a question that cannot be answered definitively (and most certainly not by a Singaporean). What can be objectively stated, however, is that its pumps are heavily subsidised by the government.

We go back to 1983 for the genesis of this, where a scheme called the 'automatic pricing mechanism' (APM) was introduced to combat the volatility (and potential exorbitance) of fuel costs. With the Malaysian government taking it upon itself to determine point-of-sale prices, the notion of 'automatic', in principle, was supposed to pass market fluctuations on to the consumer through a predetermined formula. Increased market prices would be cushioned for consumers; decreases would see subsidies reduced to take the pressure off government expenditure.

In reality, however, fuel prices rarely changed in close tandem with market pressures. Rather, over the years, they've crept up a rate that hasn't quite reflected the inflation going on in most parts of the world. Some analyses have called the policy 'ad-hoc pricing' instead, noting that for a long time, the government exercised full discretion with raising or lowering subsidy levels (it was mostly the former), rather than allowing the market to do its work.

RON97 - the lifeblood of BMW M cars and Mercedes-AMGs - isn't subsidised, but still retails for far less than intermediate grades in Singapore While this was revised in 2014 with a subsidy reform plan (which also saw premium grades like RON97 petrol - the lifeblood of BMW M cars and Mercedes-AMGs - fully returning to the market's embrace), a substantial level of price 'cushioning' has remained in place. As of the time of writing, even pump operators in our other neighbours like Thailand and Indonesia sell 95 grade petrol at approximately S$1.50 - more than double the price set by Malaysia.

RON97 - the lifeblood of BMW M cars and Mercedes-AMGs - isn't subsidised, but still retails for far less than intermediate grades in Singapore While this was revised in 2014 with a subsidy reform plan (which also saw premium grades like RON97 petrol - the lifeblood of BMW M cars and Mercedes-AMGs - fully returning to the market's embrace), a substantial level of price 'cushioning' has remained in place. As of the time of writing, even pump operators in our other neighbours like Thailand and Indonesia sell 95 grade petrol at approximately S$1.50 - more than double the price set by Malaysia.

As one can imagine, however, any form of subsidisation program isn't cheap to finance - much less one for a widely used, potentially lucrative commodity. This is doubly complex for Malaysia, which is a producer and net exporter of crude oil. A surge in crude oil prices should technically add some welcome weight to government coffers, but the subsidies also mean it has to incur unimaginable costs in order to maintain the same prices for its drivers.

Last year, RM11 billion (~S$3.54 billion) was already spent on fuel subsidies. With the current crisis rocking our world, there is fear that this bill may balloon to RM28 billion (more than S$9 billion) when 2022 concludes. These are hefty amounts funded by the Malaysian government. And in turn, hefty amounts funded by Malaysian taxpayers as well - not Singaporeans.

Cars in Singapore: Also a (costly) privilege, reserved only for the wealthy

Petrol duties were raised just last year to encourage cleaner (EVs) or more fuel efficient (hybrids) cars Armed with an understanding of how petrol pump prices work, we (S-platers) should already expect to see larger amounts getting siphoned out of wallets than those of our neighbours. It stands to reason that non-fuel components are much more expensive here, considering our higher cost of living.

Petrol duties were raised just last year to encourage cleaner (EVs) or more fuel efficient (hybrids) cars Armed with an understanding of how petrol pump prices work, we (S-platers) should already expect to see larger amounts getting siphoned out of wallets than those of our neighbours. It stands to reason that non-fuel components are much more expensive here, considering our higher cost of living.

But yet another factor specific to Singapore's scene comes into the picture: Taxes.

Back in 2003, Singapore was already charging fuel duties of S$0.41 per litre for intermediate petrol grades, and S$0.44 per litre for premium ones.

They were raised once in 2015, and then again when Budget 2021 was unveiled last year - right smack in the middle of a recovering economy. Going up by 18% and 23% respectively, duties on intermediate and premium grades now stand at S$0.66 and S$0.79 per litre. (Put into context, that tax on 95-grade petrol is almost equivalent to the nett price of the same petrol in Malaysia.)

It's not that this apparent exorbitance hasn't gone unnoticed. One of the burning questions among drivers - whether operators collude to jack prices up - was actually raised in Parliament. The results of a study that investigated this? Against popular belief, pump prices actually tend to drop faster than they rise following crude oil price fluctuations.

The fact that Singapore's climate of taxes isn't the kindest to drivers has stood unchanged since the 1990s In fact, it may also comfort some to know that debates have always circulated (in official forums as well) about whether or not fuel taxes should be more forgiving towards Singaporeans. But cry foul as we may, Singapore's fuel policy doesn't actually deviate from the private vehicle-discouraging stance that the authorities have held their ground on since the early 90s.

The fact that Singapore's climate of taxes isn't the kindest to drivers has stood unchanged since the 1990s In fact, it may also comfort some to know that debates have always circulated (in official forums as well) about whether or not fuel taxes should be more forgiving towards Singaporeans. But cry foul as we may, Singapore's fuel policy doesn't actually deviate from the private vehicle-discouraging stance that the authorities have held their ground on since the early 90s.

That also means that the authorities will not budge on lowering petrol duties. With the land border reopening (and related shenanigans) colliding perfectly with the oil crisis bubbling under Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the same stance was reiterated. Calling the cutting of taxes "counter-productive", subsidising fuel was likened by the Finance Minister to subsidising a small but relatively well-off group, considering fewer than four in 10 households own a car locally.

The literal price we pay for the environment we live in

It would appear, by some stroke of curious luck, that the country with the highest fuel taxes in Southeast Asia just happens to be placed next to the country with the most subsidies - a situation ultimately influenced by the two nations' different geographies, natural resources, and politics.

But while arguing about the fairness of Singapore's car-regulation policies will leave us blue in the face without a productive resolution, there's no denying that one can get by on our island without incurring the tremendous costs of car ownership. This position is becoming even easier to defend with the boom that we've seen in car-sharing over the last few years.

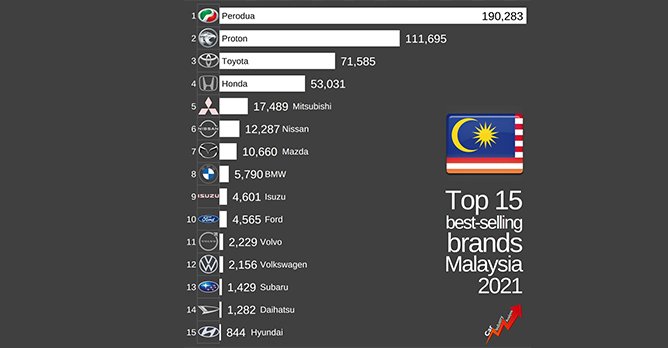

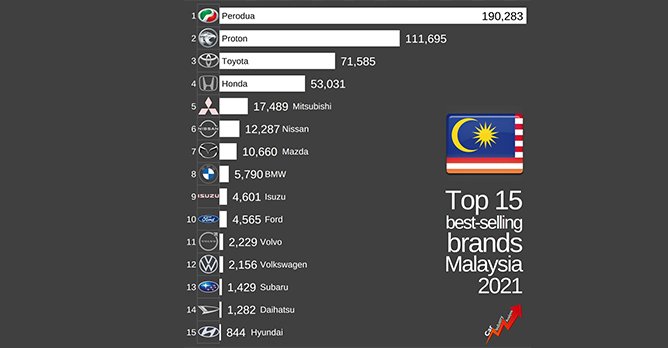

The same cannot be said of Malaysia, whose vast size makes it far more difficult to implement a public transport network extensive enough to negate car usage. Comparing their best-selling list of cars last year with ours, brand for brand, will also shed some light on the way we treat cars differently; one list certainly slants towards the mass market more than the other. (No prizes for guessing which.)

Malaysia's best-selling list of cars for 2021 was dominated by local budget brands, Perodua and Proton (Image: Car Industry Analysis) Therein, the wants versus needs dichotomy emerges again.

Malaysia's best-selling list of cars for 2021 was dominated by local budget brands, Perodua and Proton (Image: Car Industry Analysis) Therein, the wants versus needs dichotomy emerges again.

Although legitimate concerns about the opportunity costs and sustainability of Malaysia's subsidies have been voiced, we (again) cannot definitively claim that its pumps are under-priced. Conversely, we could certainly argue that Singapore's pumps are overpriced... yet this reality has become so firmly entrenched that it perhaps shouldn't be so fiercely questioned anymore.

Instead - and especially when we consider the circumstances of our neighbours - maybe the question should be: Is it justifiable to tax something that's more of a want than a need?

Painful as it may be (we're drivers ourselves), that's something worth pausing to ponder seriously.

Penny-pinching Singaporeans, it seems.

Reserved solely for the consumption of Malaysian drivers, RON95 (Research Octane Number 95, in full) has been banned from Singaporean cars since August 2010. The differences in dollars and cents may indicate why; even the most aggressive discounts applied by the most mathematically-inclined drivers will not depress one litre of 95-grade petrol below S$2.50... yet drive a few kilometres north of Woodlands, and you'll see RON95 retailing at RM2.20 per litre (that's just above S$0.70 at prevailing exchange rates).

On the surface, a full decade (and more) of enshrining this ban into law hasn't appeared sufficient in sending the message to some stubborn, errant drivers. Peeling back the issue, however, would circle us back to the innate displeasure that Singaporeans have with how petrol is priced on our shores.

All this does resurface the question of whether Singapore's pumps are overpriced - but it also begs another question we ask less frequently: Are Malaysia's pumps under-priced?

From crude oil to refined petrol: A quick explainer

After all, didn't crude oil prices plummet to sub-zero levels at one point during the pandemic? Shouldn't these fluctuations also then be passed on to us (but more of the lows, less of the highs, please)?

Yes… And no.

Undeniably, how much a barrel of crude oil costs affects the amount petrol will retail at - it's the very basic material form, after all, from which any sort of processing starts. But therein lies the catch: It needs to be refined. And refining comes with its own extra considerations.

This is why operators across Asia take reference from the Mean of Platts Singapore (MOPS), a benchmark pricing calculated by an assessment agency dedicated to refined oil products. It is from hereon that operators begin to formulate the numbers that we eventually see when we pull up to a petrol station (or on Fuel Kaki and Waze).

Naturally, however, more goes into the equation. Among other costs, wages for workers as well as land (and therefore rental) costs all find their way into the eventual retail prices for petrol as well. In 2015, a local study indicated that MOPS accounted for less than a third of what we were paying for at the pumps (it's not far-fetched to consider that this hasn't changed too drastically over the years). In Malaysia - where the industry also relies on MOPS - that figure currently stands at close to 50%.

RON95: A (costly) privilege, reserved only for the rakyat

We go back to 1983 for the genesis of this, where a scheme called the 'automatic pricing mechanism' (APM) was introduced to combat the volatility (and potential exorbitance) of fuel costs. With the Malaysian government taking it upon itself to determine point-of-sale prices, the notion of 'automatic', in principle, was supposed to pass market fluctuations on to the consumer through a predetermined formula. Increased market prices would be cushioned for consumers; decreases would see subsidies reduced to take the pressure off government expenditure.

In reality, however, fuel prices rarely changed in close tandem with market pressures. Rather, over the years, they've crept up a rate that hasn't quite reflected the inflation going on in most parts of the world. Some analyses have called the policy 'ad-hoc pricing' instead, noting that for a long time, the government exercised full discretion with raising or lowering subsidy levels (it was mostly the former), rather than allowing the market to do its work.

As one can imagine, however, any form of subsidisation program isn't cheap to finance - much less one for a widely used, potentially lucrative commodity. This is doubly complex for Malaysia, which is a producer and net exporter of crude oil. A surge in crude oil prices should technically add some welcome weight to government coffers, but the subsidies also mean it has to incur unimaginable costs in order to maintain the same prices for its drivers.

Last year, RM11 billion (~S$3.54 billion) was already spent on fuel subsidies. With the current crisis rocking our world, there is fear that this bill may balloon to RM28 billion (more than S$9 billion) when 2022 concludes. These are hefty amounts funded by the Malaysian government. And in turn, hefty amounts funded by Malaysian taxpayers as well - not Singaporeans.

Cars in Singapore: Also a (costly) privilege, reserved only for the wealthy

But yet another factor specific to Singapore's scene comes into the picture: Taxes.

Back in 2003, Singapore was already charging fuel duties of S$0.41 per litre for intermediate petrol grades, and S$0.44 per litre for premium ones.

They were raised once in 2015, and then again when Budget 2021 was unveiled last year - right smack in the middle of a recovering economy. Going up by 18% and 23% respectively, duties on intermediate and premium grades now stand at S$0.66 and S$0.79 per litre. (Put into context, that tax on 95-grade petrol is almost equivalent to the nett price of the same petrol in Malaysia.)

It's not that this apparent exorbitance hasn't gone unnoticed. One of the burning questions among drivers - whether operators collude to jack prices up - was actually raised in Parliament. The results of a study that investigated this? Against popular belief, pump prices actually tend to drop faster than they rise following crude oil price fluctuations.

That also means that the authorities will not budge on lowering petrol duties. With the land border reopening (and related shenanigans) colliding perfectly with the oil crisis bubbling under Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the same stance was reiterated. Calling the cutting of taxes "counter-productive", subsidising fuel was likened by the Finance Minister to subsidising a small but relatively well-off group, considering fewer than four in 10 households own a car locally.

The literal price we pay for the environment we live in

It would appear, by some stroke of curious luck, that the country with the highest fuel taxes in Southeast Asia just happens to be placed next to the country with the most subsidies - a situation ultimately influenced by the two nations' different geographies, natural resources, and politics.

But while arguing about the fairness of Singapore's car-regulation policies will leave us blue in the face without a productive resolution, there's no denying that one can get by on our island without incurring the tremendous costs of car ownership. This position is becoming even easier to defend with the boom that we've seen in car-sharing over the last few years.

The same cannot be said of Malaysia, whose vast size makes it far more difficult to implement a public transport network extensive enough to negate car usage. Comparing their best-selling list of cars last year with ours, brand for brand, will also shed some light on the way we treat cars differently; one list certainly slants towards the mass market more than the other. (No prizes for guessing which.)

Although legitimate concerns about the opportunity costs and sustainability of Malaysia's subsidies have been voiced, we (again) cannot definitively claim that its pumps are under-priced. Conversely, we could certainly argue that Singapore's pumps are overpriced... yet this reality has become so firmly entrenched that it perhaps shouldn't be so fiercely questioned anymore.

Instead - and especially when we consider the circumstances of our neighbours - maybe the question should be: Is it justifiable to tax something that's more of a want than a need?

Painful as it may be (we're drivers ourselves), that's something worth pausing to ponder seriously.

What do unnecessary car jacks, enforcement officers at petrol stations, and one ruffled ex-Prime Minister of Malaysia have in common?

Penny-pinching Singaporeans, it seems.

After more than a decade, pleading ignorance when refuelling illegally in Malaysia is no longer excusable The festivities that had kicked into full gear as the border reopened were dampened mere days after, as accounts of the aforementioned behaviour started to light the Internet up. One driver had raised his car on a hydraulic jack in what was likely an attempt to get more petrol into his tank. Multiple cars were also turned back for not having their tanks ¾ full. And then, there were the RON95 thieves.

After more than a decade, pleading ignorance when refuelling illegally in Malaysia is no longer excusable The festivities that had kicked into full gear as the border reopened were dampened mere days after, as accounts of the aforementioned behaviour started to light the Internet up. One driver had raised his car on a hydraulic jack in what was likely an attempt to get more petrol into his tank. Multiple cars were also turned back for not having their tanks ¾ full. And then, there were the RON95 thieves.

Reserved solely for the consumption of Malaysian drivers, RON95 (Research Octane Number 95, in full) has been banned from Singaporean cars since August 2010. The differences in dollars and cents may indicate why; even the most aggressive discounts applied by the most mathematically-inclined drivers will not depress one litre of 95-grade petrol below S$2.50... yet drive a few kilometres north of Woodlands, and you'll see RON95 retailing at RM2.20 per litre (that's just above S$0.70 at prevailing exchange rates).

On the surface, a full decade (and more) of enshrining this ban into law hasn't appeared sufficient in sending the message to some stubborn, errant drivers. Peeling back the issue, however, would circle us back to the innate displeasure that Singaporeans have with how petrol is priced on our shores.

All this does resurface the question of whether Singapore's pumps are overpriced - but it also begs another question we ask less frequently: Are Malaysia's pumps under-priced?

From crude oil to refined petrol: A quick explainer

The relentless fluctuation of crude oil prices has been intensely scrutinised over the last two years The volatility of crude oil prices has come under intense scrutiny over the last two years, spurred, no less, by catastrophic events whose effects have reverberated through the entire globe. But either direction things go, it seems the end result is that we're still bothered - ruffled when pump prices skyrocket (as barrel prices shoot through the roof), and indignant when prices don't seem to fall when they should.

The relentless fluctuation of crude oil prices has been intensely scrutinised over the last two years The volatility of crude oil prices has come under intense scrutiny over the last two years, spurred, no less, by catastrophic events whose effects have reverberated through the entire globe. But either direction things go, it seems the end result is that we're still bothered - ruffled when pump prices skyrocket (as barrel prices shoot through the roof), and indignant when prices don't seem to fall when they should.

After all, didn't crude oil prices plummet to sub-zero levels at one point during the pandemic? Shouldn't these fluctuations also then be passed on to us (but more of the lows, less of the highs, please)?

Yes… And no.

Undeniably, how much a barrel of crude oil costs affects the amount petrol will retail at - it's the very basic material form, after all, from which any sort of processing starts. But therein lies the catch: It needs to be refined. And refining comes with its own extra considerations.

This is why operators across Asia take reference from the Mean of Platts Singapore (MOPS), a benchmark pricing calculated by an assessment agency dedicated to refined oil products. It is from hereon that operators begin to formulate the numbers that we eventually see when we pull up to a petrol station (or on Fuel Kaki and Waze).

Naturally, however, more goes into the equation. Among other costs, wages for workers as well as land (and therefore rental) costs all find their way into the eventual retail prices for petrol as well. In 2015, a local study indicated that MOPS accounted for less than a third of what we were paying for at the pumps (it's not far-fetched to consider that this hasn't changed too drastically over the years). In Malaysia - where the industry also relies on MOPS - that figure currently stands at close to 50%.

RON95: A (costly) privilege, reserved only for the rakyat

To make inflation more manageable for its citizens, especially post-pandemic, the Malaysian government continues to substantially subsidise fuel Whether petrol in Malaysia is under-priced is a question that cannot be answered definitively (and most certainly not by a Singaporean). What can be objectively stated, however, is that its pumps are heavily subsidised by the government.

To make inflation more manageable for its citizens, especially post-pandemic, the Malaysian government continues to substantially subsidise fuel Whether petrol in Malaysia is under-priced is a question that cannot be answered definitively (and most certainly not by a Singaporean). What can be objectively stated, however, is that its pumps are heavily subsidised by the government.

We go back to 1983 for the genesis of this, where a scheme called the 'automatic pricing mechanism' (APM) was introduced to combat the volatility (and potential exorbitance) of fuel costs. With the Malaysian government taking it upon itself to determine point-of-sale prices, the notion of 'automatic', in principle, was supposed to pass market fluctuations on to the consumer through a predetermined formula. Increased market prices would be cushioned for consumers; decreases would see subsidies reduced to take the pressure off government expenditure.

In reality, however, fuel prices rarely changed in close tandem with market pressures. Rather, over the years, they've crept up a rate that hasn't quite reflected the inflation going on in most parts of the world. Some analyses have called the policy 'ad-hoc pricing' instead, noting that for a long time, the government exercised full discretion with raising or lowering subsidy levels (it was mostly the former), rather than allowing the market to do its work.

RON97 - the lifeblood of BMW M cars and Mercedes-AMGs - isn't subsidised, but still retails for far less than intermediate grades in Singapore While this was revised in 2014 with a subsidy reform plan (which also saw premium grades like RON97 petrol - the lifeblood of BMW M cars and Mercedes-AMGs - fully returning to the market's embrace), a substantial level of price 'cushioning' has remained in place. As of the time of writing, even pump operators in our other neighbours like Thailand and Indonesia sell 95 grade petrol at approximately S$1.50 - more than double the price set by Malaysia.

RON97 - the lifeblood of BMW M cars and Mercedes-AMGs - isn't subsidised, but still retails for far less than intermediate grades in Singapore While this was revised in 2014 with a subsidy reform plan (which also saw premium grades like RON97 petrol - the lifeblood of BMW M cars and Mercedes-AMGs - fully returning to the market's embrace), a substantial level of price 'cushioning' has remained in place. As of the time of writing, even pump operators in our other neighbours like Thailand and Indonesia sell 95 grade petrol at approximately S$1.50 - more than double the price set by Malaysia.

As one can imagine, however, any form of subsidisation program isn't cheap to finance - much less one for a widely used, potentially lucrative commodity. This is doubly complex for Malaysia, which is a producer and net exporter of crude oil. A surge in crude oil prices should technically add some welcome weight to government coffers, but the subsidies also mean it has to incur unimaginable costs in order to maintain the same prices for its drivers.

Last year, RM11 billion (~S$3.54 billion) was already spent on fuel subsidies. With the current crisis rocking our world, there is fear that this bill may balloon to RM28 billion (more than S$9 billion) when 2022 concludes. These are hefty amounts funded by the Malaysian government. And in turn, hefty amounts funded by Malaysian taxpayers as well - not Singaporeans.

Cars in Singapore: Also a (costly) privilege, reserved only for the wealthy

Petrol duties were raised just last year to encourage cleaner (EVs) or more fuel efficient (hybrids) cars Armed with an understanding of how petrol pump prices work, we (S-platers) should already expect to see larger amounts getting siphoned out of wallets than those of our neighbours. It stands to reason that non-fuel components are much more expensive here, considering our higher cost of living.

Petrol duties were raised just last year to encourage cleaner (EVs) or more fuel efficient (hybrids) cars Armed with an understanding of how petrol pump prices work, we (S-platers) should already expect to see larger amounts getting siphoned out of wallets than those of our neighbours. It stands to reason that non-fuel components are much more expensive here, considering our higher cost of living.

But yet another factor specific to Singapore's scene comes into the picture: Taxes.

Back in 2003, Singapore was already charging fuel duties of S$0.41 per litre for intermediate petrol grades, and S$0.44 per litre for premium ones.

They were raised once in 2015, and then again when Budget 2021 was unveiled last year - right smack in the middle of a recovering economy. Going up by 18% and 23% respectively, duties on intermediate and premium grades now stand at S$0.66 and S$0.79 per litre. (Put into context, that tax on 95-grade petrol is almost equivalent to the nett price of the same petrol in Malaysia.)

It's not that this apparent exorbitance hasn't gone unnoticed. One of the burning questions among drivers - whether operators collude to jack prices up - was actually raised in Parliament. The results of a study that investigated this? Against popular belief, pump prices actually tend to drop faster than they rise following crude oil price fluctuations.

The fact that Singapore's climate of taxes isn't the kindest to drivers has stood unchanged since the 1990s In fact, it may also comfort some to know that debates have always circulated (in official forums as well) about whether or not fuel taxes should be more forgiving towards Singaporeans. But cry foul as we may, Singapore's fuel policy doesn't actually deviate from the private vehicle-discouraging stance that the authorities have held their ground on since the early 90s.

The fact that Singapore's climate of taxes isn't the kindest to drivers has stood unchanged since the 1990s In fact, it may also comfort some to know that debates have always circulated (in official forums as well) about whether or not fuel taxes should be more forgiving towards Singaporeans. But cry foul as we may, Singapore's fuel policy doesn't actually deviate from the private vehicle-discouraging stance that the authorities have held their ground on since the early 90s.

That also means that the authorities will not budge on lowering petrol duties. With the land border reopening (and related shenanigans) colliding perfectly with the oil crisis bubbling under Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the same stance was reiterated. Calling the cutting of taxes "counter-productive", subsidising fuel was likened by the Finance Minister to subsidising a small but relatively well-off group, considering fewer than four in 10 households own a car locally.

The literal price we pay for the environment we live in

It would appear, by some stroke of curious luck, that the country with the highest fuel taxes in Southeast Asia just happens to be placed next to the country with the most subsidies - a situation ultimately influenced by the two nations' different geographies, natural resources, and politics.

But while arguing about the fairness of Singapore's car-regulation policies will leave us blue in the face without a productive resolution, there's no denying that one can get by on our island without incurring the tremendous costs of car ownership. This position is becoming even easier to defend with the boom that we've seen in car-sharing over the last few years.

The same cannot be said of Malaysia, whose vast size makes it far more difficult to implement a public transport network extensive enough to negate car usage. Comparing their best-selling list of cars last year with ours, brand for brand, will also shed some light on the way we treat cars differently; one list certainly slants towards the mass market more than the other. (No prizes for guessing which.)

Malaysia's best-selling list of cars for 2021 was dominated by local budget brands, Perodua and Proton (Image: Car Industry Analysis) Therein, the wants versus needs dichotomy emerges again.

Malaysia's best-selling list of cars for 2021 was dominated by local budget brands, Perodua and Proton (Image: Car Industry Analysis) Therein, the wants versus needs dichotomy emerges again.

Although legitimate concerns about the opportunity costs and sustainability of Malaysia's subsidies have been voiced, we (again) cannot definitively claim that its pumps are under-priced. Conversely, we could certainly argue that Singapore's pumps are overpriced... yet this reality has become so firmly entrenched that it perhaps shouldn't be so fiercely questioned anymore.

Instead - and especially when we consider the circumstances of our neighbours - maybe the question should be: Is it justifiable to tax something that's more of a want than a need?

Painful as it may be (we're drivers ourselves), that's something worth pausing to ponder seriously.

Penny-pinching Singaporeans, it seems.

Reserved solely for the consumption of Malaysian drivers, RON95 (Research Octane Number 95, in full) has been banned from Singaporean cars since August 2010. The differences in dollars and cents may indicate why; even the most aggressive discounts applied by the most mathematically-inclined drivers will not depress one litre of 95-grade petrol below S$2.50... yet drive a few kilometres north of Woodlands, and you'll see RON95 retailing at RM2.20 per litre (that's just above S$0.70 at prevailing exchange rates).

On the surface, a full decade (and more) of enshrining this ban into law hasn't appeared sufficient in sending the message to some stubborn, errant drivers. Peeling back the issue, however, would circle us back to the innate displeasure that Singaporeans have with how petrol is priced on our shores.

All this does resurface the question of whether Singapore's pumps are overpriced - but it also begs another question we ask less frequently: Are Malaysia's pumps under-priced?

From crude oil to refined petrol: A quick explainer

After all, didn't crude oil prices plummet to sub-zero levels at one point during the pandemic? Shouldn't these fluctuations also then be passed on to us (but more of the lows, less of the highs, please)?

Yes… And no.

Undeniably, how much a barrel of crude oil costs affects the amount petrol will retail at - it's the very basic material form, after all, from which any sort of processing starts. But therein lies the catch: It needs to be refined. And refining comes with its own extra considerations.

This is why operators across Asia take reference from the Mean of Platts Singapore (MOPS), a benchmark pricing calculated by an assessment agency dedicated to refined oil products. It is from hereon that operators begin to formulate the numbers that we eventually see when we pull up to a petrol station (or on Fuel Kaki and Waze).

Naturally, however, more goes into the equation. Among other costs, wages for workers as well as land (and therefore rental) costs all find their way into the eventual retail prices for petrol as well. In 2015, a local study indicated that MOPS accounted for less than a third of what we were paying for at the pumps (it's not far-fetched to consider that this hasn't changed too drastically over the years). In Malaysia - where the industry also relies on MOPS - that figure currently stands at close to 50%.

RON95: A (costly) privilege, reserved only for the rakyat

We go back to 1983 for the genesis of this, where a scheme called the 'automatic pricing mechanism' (APM) was introduced to combat the volatility (and potential exorbitance) of fuel costs. With the Malaysian government taking it upon itself to determine point-of-sale prices, the notion of 'automatic', in principle, was supposed to pass market fluctuations on to the consumer through a predetermined formula. Increased market prices would be cushioned for consumers; decreases would see subsidies reduced to take the pressure off government expenditure.

In reality, however, fuel prices rarely changed in close tandem with market pressures. Rather, over the years, they've crept up a rate that hasn't quite reflected the inflation going on in most parts of the world. Some analyses have called the policy 'ad-hoc pricing' instead, noting that for a long time, the government exercised full discretion with raising or lowering subsidy levels (it was mostly the former), rather than allowing the market to do its work.

As one can imagine, however, any form of subsidisation program isn't cheap to finance - much less one for a widely used, potentially lucrative commodity. This is doubly complex for Malaysia, which is a producer and net exporter of crude oil. A surge in crude oil prices should technically add some welcome weight to government coffers, but the subsidies also mean it has to incur unimaginable costs in order to maintain the same prices for its drivers.

Last year, RM11 billion (~S$3.54 billion) was already spent on fuel subsidies. With the current crisis rocking our world, there is fear that this bill may balloon to RM28 billion (more than S$9 billion) when 2022 concludes. These are hefty amounts funded by the Malaysian government. And in turn, hefty amounts funded by Malaysian taxpayers as well - not Singaporeans.

Cars in Singapore: Also a (costly) privilege, reserved only for the wealthy

But yet another factor specific to Singapore's scene comes into the picture: Taxes.

Back in 2003, Singapore was already charging fuel duties of S$0.41 per litre for intermediate petrol grades, and S$0.44 per litre for premium ones.

They were raised once in 2015, and then again when Budget 2021 was unveiled last year - right smack in the middle of a recovering economy. Going up by 18% and 23% respectively, duties on intermediate and premium grades now stand at S$0.66 and S$0.79 per litre. (Put into context, that tax on 95-grade petrol is almost equivalent to the nett price of the same petrol in Malaysia.)

It's not that this apparent exorbitance hasn't gone unnoticed. One of the burning questions among drivers - whether operators collude to jack prices up - was actually raised in Parliament. The results of a study that investigated this? Against popular belief, pump prices actually tend to drop faster than they rise following crude oil price fluctuations.

That also means that the authorities will not budge on lowering petrol duties. With the land border reopening (and related shenanigans) colliding perfectly with the oil crisis bubbling under Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the same stance was reiterated. Calling the cutting of taxes "counter-productive", subsidising fuel was likened by the Finance Minister to subsidising a small but relatively well-off group, considering fewer than four in 10 households own a car locally.

The literal price we pay for the environment we live in

It would appear, by some stroke of curious luck, that the country with the highest fuel taxes in Southeast Asia just happens to be placed next to the country with the most subsidies - a situation ultimately influenced by the two nations' different geographies, natural resources, and politics.

But while arguing about the fairness of Singapore's car-regulation policies will leave us blue in the face without a productive resolution, there's no denying that one can get by on our island without incurring the tremendous costs of car ownership. This position is becoming even easier to defend with the boom that we've seen in car-sharing over the last few years.

The same cannot be said of Malaysia, whose vast size makes it far more difficult to implement a public transport network extensive enough to negate car usage. Comparing their best-selling list of cars last year with ours, brand for brand, will also shed some light on the way we treat cars differently; one list certainly slants towards the mass market more than the other. (No prizes for guessing which.)

Although legitimate concerns about the opportunity costs and sustainability of Malaysia's subsidies have been voiced, we (again) cannot definitively claim that its pumps are under-priced. Conversely, we could certainly argue that Singapore's pumps are overpriced... yet this reality has become so firmly entrenched that it perhaps shouldn't be so fiercely questioned anymore.

Instead - and especially when we consider the circumstances of our neighbours - maybe the question should be: Is it justifiable to tax something that's more of a want than a need?

Painful as it may be (we're drivers ourselves), that's something worth pausing to ponder seriously.

Thank You For Your Subscription.