Dangerous driving: When will we learn?

17 Jan 2022|10,698 views

After we bore witness to the horrific loss of five young lives on the eve of Chinese New Year last year, the recent news about the passing of a 59-year old motorist just before Christmas is a difficult pill to swallow, most pronounced because he had been completely innocent. A 33-year old male driver has been arrested for dangerous driving causing death.

Looking back, it's not difficult to feel the shock even at this point, nor fearfully wonder if it could have been a loved one, a friend - even us, ourselves - caught in the situation: Driving around with appropriate caution, only to encounter someone else who couldn't say the same.

It also brings us back to the question of why some people on our roads exhibit such irresponsibility - and how we can reach a point where it doesn't happen anymore.

Digging deep into dangerous driving

While attributing blame to the indefensible idiocy of the speeding motorist in the accident would surely not be a matter of dispute, the psychology behind dangerous driving is actually more nuanced and varied. Why do people drive recklessly?

That's quite a large question to unpack... so let's perhaps rewind slightly first to how we should even demarcate dangerous driving.

Is it speeding? If so, going by strict definitions, doing 95km/h where the limit is 90km/h would already count. While most of us would regard this as relatively harmless, however, even this could mark the start of a slippery slope.

"I'm sure this fella will back off if I don't let him filter in", was what probably went through the mind of this camcar driver, seconds before impact People who play with the limits a bit while already on the fast lane are, naturally, unlikely to be P-plate drivers. Rather, they are drivers who have already grown comfortable enough on the road. In line with what this article suggests, what could follow (as a natural progression) is an overestimation of our driving skills, as well our sense of safety.

"I'm sure this fella will back off if I don't let him filter in", was what probably went through the mind of this camcar driver, seconds before impact People who play with the limits a bit while already on the fast lane are, naturally, unlikely to be P-plate drivers. Rather, they are drivers who have already grown comfortable enough on the road. In line with what this article suggests, what could follow (as a natural progression) is an overestimation of our driving skills, as well our sense of safety.

As being on the road becomes more intuitive over time, we apparently start to take some things for granted. Can you be certain, for instance, that you're giving yourself enough space to brake without kissing the road-hogging car in front? Or that you'll have enough time to slow down if the lights up ahead suddenly slip to amber?

Most of us also think of our driving skills as above average, which, going by the technical understanding of averages… is impossible. (Experts also refer to this as the optimism bias.) We then start to assume over time, understandably, that driving is a simple and straightforward activity (it isn't). Naturally, it's not difficult to see how erroneous judgement can follow.

People who drive dangerously have been observed to be more sensation seeking, or view speeding as part of their identity But dangerous driving is, without doubt, infinitely more egregious than just doing 83km/h in the KPE, isn't it? It's swerving in and out of traffic with barely inches to spare between other cars; or driving after a couple of glasses too many. It's not just about raw numbers too. Doing 85km/h where the speed limit is 70km/h has led us down some very tragic paths.

People who drive dangerously have been observed to be more sensation seeking, or view speeding as part of their identity But dangerous driving is, without doubt, infinitely more egregious than just doing 83km/h in the KPE, isn't it? It's swerving in and out of traffic with barely inches to spare between other cars; or driving after a couple of glasses too many. It's not just about raw numbers too. Doing 85km/h where the speed limit is 70km/h has led us down some very tragic paths.

As such, we turn our attention to other pertinent issues that have emerged from observing those who have run afoul with the law.

Multiple studies, conducted on motorists charged with driving offences, have coalesced to suggest that such groups often exhibit lower levels of inhibition and self-control. This often relates to the executive function of our brains, which, broadly speaking, helps to manage behaviour.

Social norms have tended to glorify speed uncritically - with films like this one also playing a more subtle role than one might expect Other studies which have attempted to identify salient commonalities among offenders also brought up the possible existence of at-risk groups, including those who are more sensation-seeking, and who view speeding as part of their self-identity. Another group who is likely to speed without abandon? Those with road rage.

Social norms have tended to glorify speed uncritically - with films like this one also playing a more subtle role than one might expect Other studies which have attempted to identify salient commonalities among offenders also brought up the possible existence of at-risk groups, including those who are more sensation-seeking, and who view speeding as part of their self-identity. Another group who is likely to speed without abandon? Those with road rage.

Beyond that, it's undeniable that social norms tend to glorify speed. While there is most definitely a place for more unbridled driving, such as on a race track or where the environment actually allows it (Germany's Autobahncomes to mind), overarching "cultural messages" don't bother with breaking things down into Terms and Conditions of Driving Quickly. There's no "Speed is fun only when it's safe"; just "Speed is fun", full stop. That can be problematic.

Bringing the numbers down: What actually works?

Even after amending the Road Traffic Act, current penalities in Singapore are less harsh than in Hong Kong or the U.K. As the first order of business, hard regulation has often been turned to to keep us in check. Yet one often wonders if legal justice alone is a sturdy enough pillar to hold everything up in place.

Even after amending the Road Traffic Act, current penalities in Singapore are less harsh than in Hong Kong or the U.K. As the first order of business, hard regulation has often been turned to to keep us in check. Yet one often wonders if legal justice alone is a sturdy enough pillar to hold everything up in place.

In 2019, Singapore's Road Traffic Act was amended to bring about increased fines and longer jail terms for dangerous driving (a Minister had mentioned, rightfully, that previous penalties were "manifestly inadequate"). For instance, instead of a maximum term of five years, first-time offenders of dangerous driving causing death now face a possible eight-year jail term.

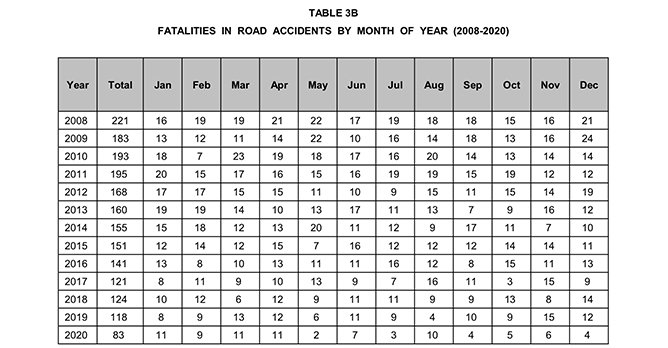

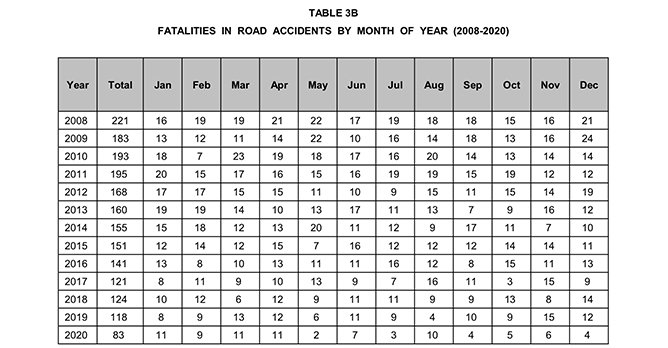

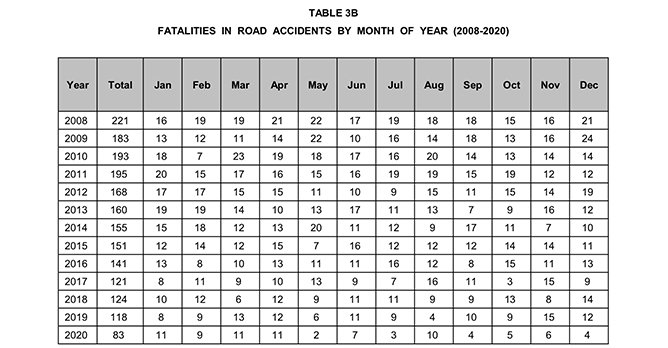

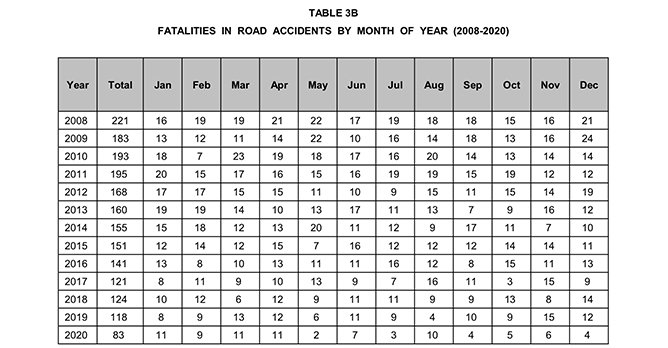

Singapore's road fatalities have thankfully dwindled from their 2008 levels - but not quite quickly enough Nonetheless, questions have arisen on whether deterrence alone may be sharp enough to cut through the heart of the problem. Some evidence suggests that people only adjust their behaviour temporarily before reverting to their recklessness after passing the watchful eye of a police officer or camera. (Most of us are probably guilty of that.)

Singapore's road fatalities have thankfully dwindled from their 2008 levels - but not quite quickly enough Nonetheless, questions have arisen on whether deterrence alone may be sharp enough to cut through the heart of the problem. Some evidence suggests that people only adjust their behaviour temporarily before reverting to their recklessness after passing the watchful eye of a police officer or camera. (Most of us are probably guilty of that.)

While Singapore's road fatality rates per capita are actually quite low when stacked up against other territories, it is universally and gravely recognised that human lives cannot be distilled to numbers and figures. Even one fatality is one too many.

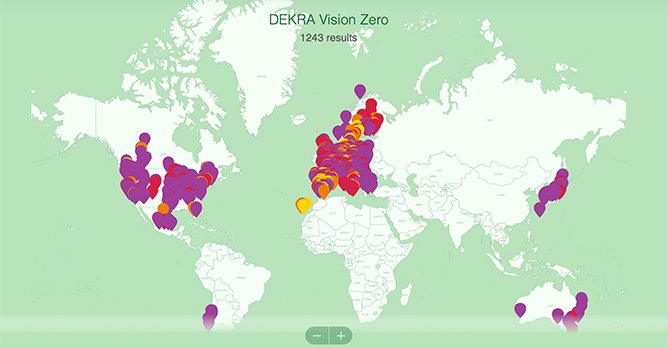

To uplift positive examples of road safety, an interactive map created by the Dekra Vision Zero project actively identifies towns and cities around the world which have managed to achieve zero fatalities - some, for more than a decade. Naturally, most of these places are less densely populated (Gothenburg is on the map; New York City isn't). But there are still invaluable insights to be gleaned.

Instead of dictating that people cannot go above speed limit, an important common thread running through all of the success stories thus far is an important strategy. Rather than brandish the whip of punishment singularly, the idea of engineering the environment goes about the job with more subtlety - by making it impossible for you to speed without you actively knowing it.

The two-way Hougang St 21 was previously a wide open stretch of road (spot the L-plate Toyota Vioses from ComfortDelgro chilling near the kerb) If you also attended driving lessons with ComfortDelgro and had Kovan as your pick-up point in the mid-2010s, you will surely remember switching over with your instructor at the wide two-way street along Hougang St 21.

The two-way Hougang St 21 was previously a wide open stretch of road (spot the L-plate Toyota Vioses from ComfortDelgro chilling near the kerb) If you also attended driving lessons with ComfortDelgro and had Kovan as your pick-up point in the mid-2010s, you will surely remember switching over with your instructor at the wide two-way street along Hougang St 21.

But guess what wide, open roads encourage? Speed.

Things have changed. As part of the LTA's efforts since 2014 to introduce Silver Zones - featuring safer and more user-friendly stretches of road for elderly pedestrians - a divider replete with grass patches and pedestrian crossing paths now snakes down the middle, making it virtually impossible to keep your foot on the gas as you twist and turn your way down the street. Mission accomplished.

Chicanes, a snaking divider, humps and walking paths, now feature as part of the Silver Zone reformation Coupled with these valuable changes to infrastructure, perhaps the way we frame dangerous driving has to shift too.

Chicanes, a snaking divider, humps and walking paths, now feature as part of the Silver Zone reformation Coupled with these valuable changes to infrastructure, perhaps the way we frame dangerous driving has to shift too.

Arriving at the answer to how we can break and remould societal beliefs - especially misguided ones that paint dangerous driving out to be cool - is admittedly like driving through a thick fog. At the very least, however, there will be value to be found in increasingly posing the right questions.

Rather than ask "What can we do to scare would-be offenders?", why not start with "What drives would-be offenders?"? If they haven't been already, specified rehabilitative interventions for offenders should also come into practice, and be closely guided by more in-depth attempts to demystify the motivating and demotivating factors around dangerous driving.

The road to zero

While it's a pity that most cars don't have the space to unlock their full potential here, there is really no excusing recklessness on our roads We, as car lovers, will be the last people to denigrate the thrills that performance cars bring.

While it's a pity that most cars don't have the space to unlock their full potential here, there is really no excusing recklessness on our roads We, as car lovers, will be the last people to denigrate the thrills that performance cars bring.

The unfortunately and harsh reality, however, is that there's virtually no space for that in Singapore. To cry foul and pretend otherwise is foolish - and too often fatal.

Harsher penalties will and should continue to ensure that punishment is meted out in every last drop to motorists who value neither their own lives nor those of others on the road. But change will only start to be truly effected when we nip the problem at its bud - and that means reshaping our attitudes towards our cars, while literally reshaping our roads.

Instead of waving an accusatory finger at other drivers on the road, it would maybe also do us all some good to take a step back and reflect on our own behaviour from time to time. At risk of sounding like a government-sponsored ad (we promise you this isn't), everyone has a part to play - including yours truly.

Here's to the day that we see Singapore's pin on the Vision Zero map.

Looking back, it's not difficult to feel the shock even at this point, nor fearfully wonder if it could have been a loved one, a friend - even us, ourselves - caught in the situation: Driving around with appropriate caution, only to encounter someone else who couldn't say the same.

It also brings us back to the question of why some people on our roads exhibit such irresponsibility - and how we can reach a point where it doesn't happen anymore.

Digging deep into dangerous driving

While attributing blame to the indefensible idiocy of the speeding motorist in the accident would surely not be a matter of dispute, the psychology behind dangerous driving is actually more nuanced and varied. Why do people drive recklessly?

That's quite a large question to unpack... so let's perhaps rewind slightly first to how we should even demarcate dangerous driving.

Is it speeding? If so, going by strict definitions, doing 95km/h where the limit is 90km/h would already count. While most of us would regard this as relatively harmless, however, even this could mark the start of a slippery slope.

As being on the road becomes more intuitive over time, we apparently start to take some things for granted. Can you be certain, for instance, that you're giving yourself enough space to brake without kissing the road-hogging car in front? Or that you'll have enough time to slow down if the lights up ahead suddenly slip to amber?

Most of us also think of our driving skills as above average, which, going by the technical understanding of averages… is impossible. (Experts also refer to this as the optimism bias.) We then start to assume over time, understandably, that driving is a simple and straightforward activity (it isn't). Naturally, it's not difficult to see how erroneous judgement can follow.

As such, we turn our attention to other pertinent issues that have emerged from observing those who have run afoul with the law.

Multiple studies, conducted on motorists charged with driving offences, have coalesced to suggest that such groups often exhibit lower levels of inhibition and self-control. This often relates to the executive function of our brains, which, broadly speaking, helps to manage behaviour.

Beyond that, it's undeniable that social norms tend to glorify speed. While there is most definitely a place for more unbridled driving, such as on a race track or where the environment actually allows it (Germany's Autobahncomes to mind), overarching "cultural messages" don't bother with breaking things down into Terms and Conditions of Driving Quickly. There's no "Speed is fun only when it's safe"; just "Speed is fun", full stop. That can be problematic.

Bringing the numbers down: What actually works?

In 2019, Singapore's Road Traffic Act was amended to bring about increased fines and longer jail terms for dangerous driving (a Minister had mentioned, rightfully, that previous penalties were "manifestly inadequate"). For instance, instead of a maximum term of five years, first-time offenders of dangerous driving causing death now face a possible eight-year jail term.

While Singapore's road fatality rates per capita are actually quite low when stacked up against other territories, it is universally and gravely recognised that human lives cannot be distilled to numbers and figures. Even one fatality is one too many.

To uplift positive examples of road safety, an interactive map created by the Dekra Vision Zero project actively identifies towns and cities around the world which have managed to achieve zero fatalities - some, for more than a decade. Naturally, most of these places are less densely populated (Gothenburg is on the map; New York City isn't). But there are still invaluable insights to be gleaned.

Instead of dictating that people cannot go above speed limit, an important common thread running through all of the success stories thus far is an important strategy. Rather than brandish the whip of punishment singularly, the idea of engineering the environment goes about the job with more subtlety - by making it impossible for you to speed without you actively knowing it.

But guess what wide, open roads encourage? Speed.

Things have changed. As part of the LTA's efforts since 2014 to introduce Silver Zones - featuring safer and more user-friendly stretches of road for elderly pedestrians - a divider replete with grass patches and pedestrian crossing paths now snakes down the middle, making it virtually impossible to keep your foot on the gas as you twist and turn your way down the street. Mission accomplished.

Arriving at the answer to how we can break and remould societal beliefs - especially misguided ones that paint dangerous driving out to be cool - is admittedly like driving through a thick fog. At the very least, however, there will be value to be found in increasingly posing the right questions.

Rather than ask "What can we do to scare would-be offenders?", why not start with "What drives would-be offenders?"? If they haven't been already, specified rehabilitative interventions for offenders should also come into practice, and be closely guided by more in-depth attempts to demystify the motivating and demotivating factors around dangerous driving.

The road to zero

The unfortunately and harsh reality, however, is that there's virtually no space for that in Singapore. To cry foul and pretend otherwise is foolish - and too often fatal.

Harsher penalties will and should continue to ensure that punishment is meted out in every last drop to motorists who value neither their own lives nor those of others on the road. But change will only start to be truly effected when we nip the problem at its bud - and that means reshaping our attitudes towards our cars, while literally reshaping our roads.

Instead of waving an accusatory finger at other drivers on the road, it would maybe also do us all some good to take a step back and reflect on our own behaviour from time to time. At risk of sounding like a government-sponsored ad (we promise you this isn't), everyone has a part to play - including yours truly.

Here's to the day that we see Singapore's pin on the Vision Zero map.

After we bore witness to the horrific loss of five young lives on the eve of Chinese New Year last year, the recent news about the passing of a 59-year old motorist just before Christmas is a difficult pill to swallow, most pronounced because he had been completely innocent. A 33-year old male driver has been arrested for dangerous driving causing death.

Looking back, it's not difficult to feel the shock even at this point, nor fearfully wonder if it could have been a loved one, a friend - even us, ourselves - caught in the situation: Driving around with appropriate caution, only to encounter someone else who couldn't say the same.

It also brings us back to the question of why some people on our roads exhibit such irresponsibility - and how we can reach a point where it doesn't happen anymore.

Digging deep into dangerous driving

While attributing blame to the indefensible idiocy of the speeding motorist in the accident would surely not be a matter of dispute, the psychology behind dangerous driving is actually more nuanced and varied. Why do people drive recklessly?

That's quite a large question to unpack... so let's perhaps rewind slightly first to how we should even demarcate dangerous driving.

Is it speeding? If so, going by strict definitions, doing 95km/h where the limit is 90km/h would already count. While most of us would regard this as relatively harmless, however, even this could mark the start of a slippery slope.

"I'm sure this fella will back off if I don't let him filter in", was what probably went through the mind of this camcar driver, seconds before impact People who play with the limits a bit while already on the fast lane are, naturally, unlikely to be P-plate drivers. Rather, they are drivers who have already grown comfortable enough on the road. In line with what this article suggests, what could follow (as a natural progression) is an overestimation of our driving skills, as well our sense of safety.

"I'm sure this fella will back off if I don't let him filter in", was what probably went through the mind of this camcar driver, seconds before impact People who play with the limits a bit while already on the fast lane are, naturally, unlikely to be P-plate drivers. Rather, they are drivers who have already grown comfortable enough on the road. In line with what this article suggests, what could follow (as a natural progression) is an overestimation of our driving skills, as well our sense of safety.

As being on the road becomes more intuitive over time, we apparently start to take some things for granted. Can you be certain, for instance, that you're giving yourself enough space to brake without kissing the road-hogging car in front? Or that you'll have enough time to slow down if the lights up ahead suddenly slip to amber?

Most of us also think of our driving skills as above average, which, going by the technical understanding of averages… is impossible. (Experts also refer to this as the optimism bias.) We then start to assume over time, understandably, that driving is a simple and straightforward activity (it isn't). Naturally, it's not difficult to see how erroneous judgement can follow.

People who drive dangerously have been observed to be more sensation seeking, or view speeding as part of their identity But dangerous driving is, without doubt, infinitely more egregious than just doing 83km/h in the KPE, isn't it? It's swerving in and out of traffic with barely inches to spare between other cars; or driving after a couple of glasses too many. It's not just about raw numbers too. Doing 85km/h where the speed limit is 70km/h has led us down some very tragic paths.

People who drive dangerously have been observed to be more sensation seeking, or view speeding as part of their identity But dangerous driving is, without doubt, infinitely more egregious than just doing 83km/h in the KPE, isn't it? It's swerving in and out of traffic with barely inches to spare between other cars; or driving after a couple of glasses too many. It's not just about raw numbers too. Doing 85km/h where the speed limit is 70km/h has led us down some very tragic paths.

As such, we turn our attention to other pertinent issues that have emerged from observing those who have run afoul with the law.

Multiple studies, conducted on motorists charged with driving offences, have coalesced to suggest that such groups often exhibit lower levels of inhibition and self-control. This often relates to the executive function of our brains, which, broadly speaking, helps to manage behaviour.

Social norms have tended to glorify speed uncritically - with films like this one also playing a more subtle role than one might expect Other studies which have attempted to identify salient commonalities among offenders also brought up the possible existence of at-risk groups, including those who are more sensation-seeking, and who view speeding as part of their self-identity. Another group who is likely to speed without abandon? Those with road rage.

Social norms have tended to glorify speed uncritically - with films like this one also playing a more subtle role than one might expect Other studies which have attempted to identify salient commonalities among offenders also brought up the possible existence of at-risk groups, including those who are more sensation-seeking, and who view speeding as part of their self-identity. Another group who is likely to speed without abandon? Those with road rage.

Beyond that, it's undeniable that social norms tend to glorify speed. While there is most definitely a place for more unbridled driving, such as on a race track or where the environment actually allows it (Germany's Autobahncomes to mind), overarching "cultural messages" don't bother with breaking things down into Terms and Conditions of Driving Quickly. There's no "Speed is fun only when it's safe"; just "Speed is fun", full stop. That can be problematic.

Bringing the numbers down: What actually works?

Even after amending the Road Traffic Act, current penalities in Singapore are less harsh than in Hong Kong or the U.K. As the first order of business, hard regulation has often been turned to to keep us in check. Yet one often wonders if legal justice alone is a sturdy enough pillar to hold everything up in place.

Even after amending the Road Traffic Act, current penalities in Singapore are less harsh than in Hong Kong or the U.K. As the first order of business, hard regulation has often been turned to to keep us in check. Yet one often wonders if legal justice alone is a sturdy enough pillar to hold everything up in place.

In 2019, Singapore's Road Traffic Act was amended to bring aboutincreased fines and longer jail terms for dangerous driving (a Minister had mentioned, rightfully, that previous penalties were "manifestly inadequate"). For instance, instead of a maximum term of five years, first-time offenders of dangerous driving causing death now face a possible eight-year jail term.

Singapore's road fatalities have thankfully dwindled from their 2008 levels - but not quite quickly enough Nonetheless, questions have arisen on whether deterrence alone may be sharp enough to cut through the heart of the problem. Some evidence suggests that people only adjust their behaviour temporarily before reverting to their recklessness after passing the watchful eye of a police officer or camera. (Most of us are probably guilty of that.)

Singapore's road fatalities have thankfully dwindled from their 2008 levels - but not quite quickly enough Nonetheless, questions have arisen on whether deterrence alone may be sharp enough to cut through the heart of the problem. Some evidence suggests that people only adjust their behaviour temporarily before reverting to their recklessness after passing the watchful eye of a police officer or camera. (Most of us are probably guilty of that.)

While Singapore's road fatality rates per capita are actually quite low when stacked up against other territories, it is universally and gravely recognised that human lives cannot be distilled to numbers and figures. Even one fatality is one too many.

To uplift positive examples of road safety, an interactive map created by the Dekra Vision Zero project actively identifies towns and cities around the world which have managed to achieve zero fatalities - some, for more than a decade. Naturally, most of these places are less densely populated (Gothenburg is on the map; New York City isn't). But there are still invaluable insights to be gleaned.

Instead of dictating that people cannot go above speed limit, an important common thread running through all of the success stories thus far is an important strategy. Rather than brandish the whip of punishment singularly, the idea of engineering the environment goes about the job with more subtlety - by making it impossible for you to speed without you actively knowing it.

The two-way Hougang St 21 was previously a wide open stretch of road (spot the L-plate Toyota Vioses from ComfortDelgro chilling near the kerb) If you also attended driving lessons with ComfortDelgro and had Kovan as your pick-up point in the mid-2010s, you will surely remember switching over with your instructor at the wide two-way street along Hougang St 21.

The two-way Hougang St 21 was previously a wide open stretch of road (spot the L-plate Toyota Vioses from ComfortDelgro chilling near the kerb) If you also attended driving lessons with ComfortDelgro and had Kovan as your pick-up point in the mid-2010s, you will surely remember switching over with your instructor at the wide two-way street along Hougang St 21.

But guess what wide, open roads encourage? Speed.

Things have changed. As part of the LTA's efforts since 2014 to introduce Silver Zones - featuring safer and more user-friendly stretches of road for elderly pedestrians - a divider replete with grass patches and pedestrian crossing paths now snakes down the middle, making it virtually impossible to keep your foot on the gas as you twist and turn your way down the street. Mission accomplished.

Chicanes, a snaking divider, humps and walking paths, now feature as part of the Silver Zone reformation Coupled with these valuable changes to infrastructure, perhaps the way we frame dangerous driving has to shift too.

Chicanes, a snaking divider, humps and walking paths, now feature as part of the Silver Zone reformation Coupled with these valuable changes to infrastructure, perhaps the way we frame dangerous driving has to shift too.

Arriving at the answer to how we can break and remould societal beliefs - especially misguided ones that paint dangerous driving out to be cool - is admittedly like driving through a thick fog. At the very least, however, there will be value to be found in increasingly posing the right questions.

Rather than ask "What can we do to scare would-be offenders?", why not start with "What drives would-be offenders?"? If they haven't been already, specified rehabilitative interventions for offenders should also come into practice, and be closely guided by more in-depth attempts to demystify the motivating and demotivating factors around dangerous driving.

The road to zero

While it's a pity that most cars don't have the space to unlock their full potential here, there is really no excusing recklessness on our roads We, as car lovers, will be the last people to denigrate the thrills that performance cars bring.

While it's a pity that most cars don't have the space to unlock their full potential here, there is really no excusing recklessness on our roads We, as car lovers, will be the last people to denigrate the thrills that performance cars bring.

The unfortunately and harsh reality, however, is that there's virtually no space for that in Singapore. To cry foul and pretend otherwise is foolish - and too often fatal.

Harsher penalties will and should continue to ensure that punishment is meted out in every last drop to motorists who value neither their own lives nor those of others on the road. But change will only start to be truly effected when we nip the problem at its bud - and that means reshaping our attitudes towards our cars, while literally reshaping our roads.

Instead of waving an accusatory finger at other drivers on the road, it would maybe also do us all some good to take a step back and reflect on our own behaviour from time to time. At risk of sounding like a government-sponsored ad (we promise you this isn't), everyone has a part to play - including yours truly.

Here's to the day that we see Singapore's pin on the Vision Zero map.

Looking back, it's not difficult to feel the shock even at this point, nor fearfully wonder if it could have been a loved one, a friend - even us, ourselves - caught in the situation: Driving around with appropriate caution, only to encounter someone else who couldn't say the same.

It also brings us back to the question of why some people on our roads exhibit such irresponsibility - and how we can reach a point where it doesn't happen anymore.

Digging deep into dangerous driving

While attributing blame to the indefensible idiocy of the speeding motorist in the accident would surely not be a matter of dispute, the psychology behind dangerous driving is actually more nuanced and varied. Why do people drive recklessly?

That's quite a large question to unpack... so let's perhaps rewind slightly first to how we should even demarcate dangerous driving.

Is it speeding? If so, going by strict definitions, doing 95km/h where the limit is 90km/h would already count. While most of us would regard this as relatively harmless, however, even this could mark the start of a slippery slope.

As being on the road becomes more intuitive over time, we apparently start to take some things for granted. Can you be certain, for instance, that you're giving yourself enough space to brake without kissing the road-hogging car in front? Or that you'll have enough time to slow down if the lights up ahead suddenly slip to amber?

Most of us also think of our driving skills as above average, which, going by the technical understanding of averages… is impossible. (Experts also refer to this as the optimism bias.) We then start to assume over time, understandably, that driving is a simple and straightforward activity (it isn't). Naturally, it's not difficult to see how erroneous judgement can follow.

As such, we turn our attention to other pertinent issues that have emerged from observing those who have run afoul with the law.

Multiple studies, conducted on motorists charged with driving offences, have coalesced to suggest that such groups often exhibit lower levels of inhibition and self-control. This often relates to the executive function of our brains, which, broadly speaking, helps to manage behaviour.

Beyond that, it's undeniable that social norms tend to glorify speed. While there is most definitely a place for more unbridled driving, such as on a race track or where the environment actually allows it (Germany's Autobahncomes to mind), overarching "cultural messages" don't bother with breaking things down into Terms and Conditions of Driving Quickly. There's no "Speed is fun only when it's safe"; just "Speed is fun", full stop. That can be problematic.

Bringing the numbers down: What actually works?

In 2019, Singapore's Road Traffic Act was amended to bring aboutincreased fines and longer jail terms for dangerous driving (a Minister had mentioned, rightfully, that previous penalties were "manifestly inadequate"). For instance, instead of a maximum term of five years, first-time offenders of dangerous driving causing death now face a possible eight-year jail term.

While Singapore's road fatality rates per capita are actually quite low when stacked up against other territories, it is universally and gravely recognised that human lives cannot be distilled to numbers and figures. Even one fatality is one too many.

To uplift positive examples of road safety, an interactive map created by the Dekra Vision Zero project actively identifies towns and cities around the world which have managed to achieve zero fatalities - some, for more than a decade. Naturally, most of these places are less densely populated (Gothenburg is on the map; New York City isn't). But there are still invaluable insights to be gleaned.

Instead of dictating that people cannot go above speed limit, an important common thread running through all of the success stories thus far is an important strategy. Rather than brandish the whip of punishment singularly, the idea of engineering the environment goes about the job with more subtlety - by making it impossible for you to speed without you actively knowing it.

But guess what wide, open roads encourage? Speed.

Things have changed. As part of the LTA's efforts since 2014 to introduce Silver Zones - featuring safer and more user-friendly stretches of road for elderly pedestrians - a divider replete with grass patches and pedestrian crossing paths now snakes down the middle, making it virtually impossible to keep your foot on the gas as you twist and turn your way down the street. Mission accomplished.

Arriving at the answer to how we can break and remould societal beliefs - especially misguided ones that paint dangerous driving out to be cool - is admittedly like driving through a thick fog. At the very least, however, there will be value to be found in increasingly posing the right questions.

Rather than ask "What can we do to scare would-be offenders?", why not start with "What drives would-be offenders?"? If they haven't been already, specified rehabilitative interventions for offenders should also come into practice, and be closely guided by more in-depth attempts to demystify the motivating and demotivating factors around dangerous driving.

The road to zero

The unfortunately and harsh reality, however, is that there's virtually no space for that in Singapore. To cry foul and pretend otherwise is foolish - and too often fatal.

Harsher penalties will and should continue to ensure that punishment is meted out in every last drop to motorists who value neither their own lives nor those of others on the road. But change will only start to be truly effected when we nip the problem at its bud - and that means reshaping our attitudes towards our cars, while literally reshaping our roads.

Instead of waving an accusatory finger at other drivers on the road, it would maybe also do us all some good to take a step back and reflect on our own behaviour from time to time. At risk of sounding like a government-sponsored ad (we promise you this isn't), everyone has a part to play - including yours truly.

Here's to the day that we see Singapore's pin on the Vision Zero map.

Thank You For Your Subscription.