Singapore's outdated COE system desperately needs fixing

15 Sep 2022|81,216 views

In spite of how regularly we complain about the punitive financial devastation that the COE system inflicts on car buyers (especially right now), we cannot fundamentally dispute that the system works in its explicit and implicit intent - to control the overall population of cars on the road, as well as, of course, to generate plenty of revenue for the Government.

But, it is also high time to recognise that the COE system as constituted is outdated, and desperately needs to be relooked and arguably overhauled.

A relic of a past gone by

The COE mechanic was first put into effect in 1990, as part of the Vehicle Quota System. The automotive landscape was very different back then - electric cars were more concept than inevitable reality, private-hire and car-sharing were terms not even conceived, and 500bhp was considered hypercar performance (there are now modern SUVs that make more than 500bhp).

And, the COE system certainly reflects that time period. In a time where natural aspiration was the norm, a car's performance would generally be directly correlated to its overall displacement.

In fact, in 1990 there were a total of five passenger car categories - Cat 1 (1,000cc and below), Cat 2 (1,001cc to 1,600cc), Cat 3 (1,601cc to 2,000cc), Cat 4 (above 2,001cc), as well as Cat 7 (open category).

And, the segmentation of categories was for "social equity reasons" (as stated in the report), so the Government's intentions was clear enough - buyers shopping in the bigger capacity, more premium segments should not be competing for COEs with buyers in the more mass-market segment.

Most of the bids, expectedly, were for Cat 2. In the July 1990 tender exercise, there were about 3,600 bids for Cat 2 - reflecting not just the fact that many cars were in that particular segment, but also the strong demand for these bread-and-butter models. It is also telling (and prescient), however, that a news report noted that "the greatest over-subscription this month appeared to be for luxury cars above 2,000cc," though it should be noted that the quota for that category was just 88.

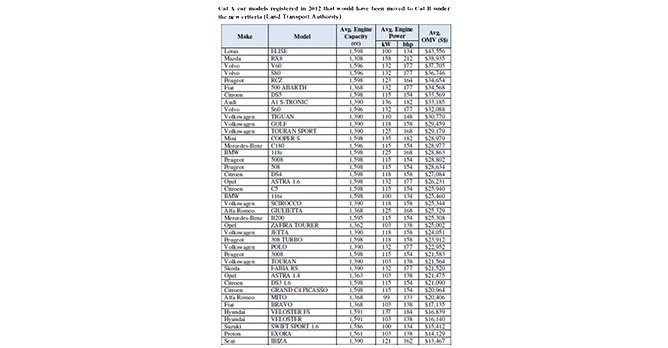

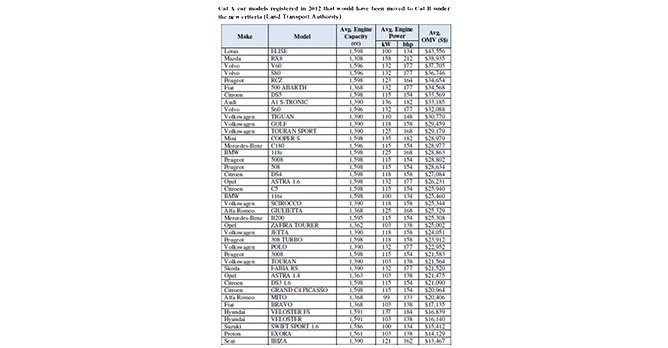

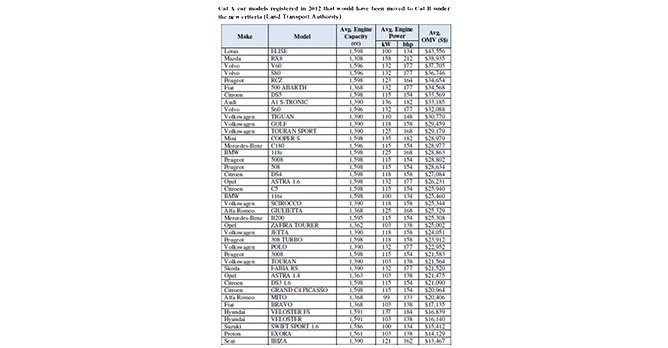

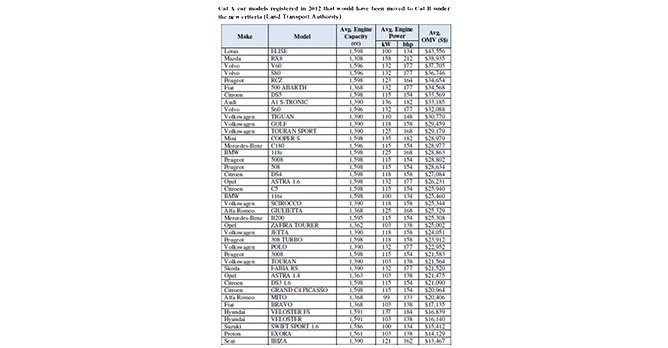

A look at the list of Cat A cars that got shunted into Cat B in 2013 reveals that most are from premium manufacturers It was only in 1999 that the system was refined into the one we recognise today (evidence that changes can indeed be made), with just three categories for passenger cars. And it was further in 2013 that the power cap of 97kW for Cat A was introduced. Premium models back in 2013, like the Mercedes-Benz C180 and the BMW 118i, would then fall into Cat B. This was done, again, with the explicit purpose of better delineating mass-market models from premium ones.

A look at the list of Cat A cars that got shunted into Cat B in 2013 reveals that most are from premium manufacturers It was only in 1999 that the system was refined into the one we recognise today (evidence that changes can indeed be made), with just three categories for passenger cars. And it was further in 2013 that the power cap of 97kW for Cat A was introduced. Premium models back in 2013, like the Mercedes-Benz C180 and the BMW 118i, would then fall into Cat B. This was done, again, with the explicit purpose of better delineating mass-market models from premium ones.

To better understand this, it's important to note the state of the automotive industry back then. In the 90s and early 2000s, many of the mass market models (chiefly from the Japanese brands) used 1.6-litre engines. These included popular cars like the Toyota Altis, Honda Civic, Mitsubishi Lancer, etc. In an era largely before widespread forced induction, premium models from the likes of the German marques had bigger displacement engines that were typically 1.8-litres and upwards (and even then, power output was still typically in the low to mid 100s for the entry-level models).

It's understandable then, for the 'cut off' mark between Cat A and B to be 1.6-litres, and 97kW. It drew a relatively obvious line between mass-market and premium models. And of course, the COE system was designed with the then market standards in mind.

Nowadays, engine displacement is certainly not directly correlated to performance. With the advent of turbocharged engines (and more recently hybrids and the like), power output has pretty much gone up across the board, even with engines getting smaller. In fact, in 2014, Ford already produced a 1.0-litre engine making 138bhp, which would have put any such car in Cat B.

As a result, the delineation between mass-market and premium models is no longer quite so clear. In fact, there are plenty of instances when models can easily straddle between the two categories depending on trim or variant.

Furthermore, with the push towards electrification, a system based around engine displacement seems even more archaic. This fails to take into account numerous relatively modern developments such as hybrids and, of course, full electric cars as well.

How to fix the COE system

Obviously, I have no policy-making jurisdiction. However, I do have some ideas as to how the COE system can be updated, not just to reflect the present realities of the automotive market, but also to better cater for changes in the future.

1. Remove the displacement cap, and raise the output cap for Cat A

The Forester's 2.0-litre engine (left) produces comparable power to the Ateca's 1.4-litre lump, proof that displacement isn't everything As cars get more technologically advanced and engine technology becomes increasingly efficient, manufacturers can get more performance out of their motors. As a consequence, displacement is no longer a good measure of performance. With turbocharging, most engines are getting smaller while output generally gets higher.

Removing the displacement cap, and using output as a singular cut-off measure, would better reflect the automotive industry in 2022 and beyond. This would still be a familiar and recognisable system to most people presenting the least radical change, though it is an imperfect solution.

The Mk 7.5 Golf was offered locally with an older 1.4-litre engine, rather than the new 1.5-litre engine being debuted Where do we draw the cut-off? Any figure would still be somewhat arbitrary (but isn't the current system also relatively arbitrary?), but one reference point can be the 110kW cap that has already been implemented for EVs.

The Mk 7.5 Golf was offered locally with an older 1.4-litre engine, rather than the new 1.5-litre engine being debuted Where do we draw the cut-off? Any figure would still be somewhat arbitrary (but isn't the current system also relatively arbitrary?), but one reference point can be the 110kW cap that has already been implemented for EVs.

One notable benefit is that this would limit instances where new models launched in Singapore still get old engines (such as was the case with the Mk 7.5 Golf and the FK Civic), simply to get the car to fit into Cat A.

This would also better account for EVs, which the Government has taken baby steps towards addressing by raising the EV-specific power cap for Cat A to 110kW.

2. Peg COE Category banding to Open Market Value (OMV)

Another (perhaps better) way to peg the COE banding is against a car's OMV. A car's OMV is a much better indication of its 'worth' or 'value', rather than performance or displacement. If the idea is that luxury goods should be taxed more (as is already the case with the tiered ARF), then wouldn't it make sense to have COE tied to car value?

The LTA has previously in 2013 rejected the idea of categorising cars based on OMV, stating that it "can fluctuate significantly for different batches of the same car, due to variations in exchange rates and car model specifications. This means the same car model can end up in Cat A or Cat B at different times."

However, this hasn't stopped some other considerations to be pegged to OMV. Presently, there are already a couple of things pegged to the $20k OMV mark - the total loan percentage allowed, as well as the first ARF tier. It could follow that the OMV cut-off for Cat A be set at the same $20k OMV figure as well.

While pegging the category cut-off at $20k would still again be somewhat arbitrary, it at least allows a fairly neat way for adjusting in the future. Adjusting the OMV cut-off upwards should be done alongside the ARF tier and loan availability, which would better account for the delineation between mass-market and premium models.

3. Remove COE banding altogether

If a car-lite future is truly on the cards, then perhaps all cars should be treated (and taxed) equally If cars are simply a luxury good altogether, and the Government is sincere about pushing towards a car-lite future, then perhaps COE banding should be removed altogether. Every car is treated the same - as a luxury good, with the respective taxation that comes with it.

If a car-lite future is truly on the cards, then perhaps all cars should be treated (and taxed) equally If cars are simply a luxury good altogether, and the Government is sincere about pushing towards a car-lite future, then perhaps COE banding should be removed altogether. Every car is treated the same - as a luxury good, with the respective taxation that comes with it.

This would provide definitive incentive to push drivers towards other means of transport, such as public transport, ride-hailing and car-sharing.

And, of course, this means there's no requirement to factor in adjustments in the future, if all cars fall into a singular COE category.

Necessary change

Of course, some of the fundamental frustrations with regards to the COE system won't go away, not unless the Government wants it to. The bidding system, wholly dependent on limited supply and excess demand, brings with it fair criticisms.

Tackling issues of supply and demand is an entirely different discussion altogether. Here, we are simply looking at the mechanics of the system and whether it is ultimately still reflective of the present market reality that we find ourselves in.

Singapore has grand ambitions of being a modern, future-ready city, even in the automotive sphere. With multiple brand regional headquarters here, and even an upcoming Hyundai manufacturing facility, it would appear that those ambitions have been largely realised.

A COE system mired in the past only serves to handicap that potential progress. And it can also be to the detriment of the customer.

If distributors are having to work with their principals to fit old engines into new cars to shoehorn new cars into old categories, we as the customer are missing out on the newest and best capabilities that technological progress and advancement has to offer.

If the automotive market was still stuck with a COE system firmly lodged in the past, that would just be shooting ourselves in the foot. It's past time for change.

In 2013, then Transport Minister Lui Tuck Yew said, "This differentiation between Cat A and Cat B is certainly an improvement over what we have today, but we have to continually re-look and adjust and revise it accordingly."

Let's hope that the continued revision and adjustments actually happen. It's happened before, so it certainly can (and needs to) happen again.

But, it is also high time to recognise that the COE system as constituted is outdated, and desperately needs to be relooked and arguably overhauled.

A relic of a past gone by

The COE mechanic was first put into effect in 1990, as part of the Vehicle Quota System. The automotive landscape was very different back then - electric cars were more concept than inevitable reality, private-hire and car-sharing were terms not even conceived, and 500bhp was considered hypercar performance (there are now modern SUVs that make more than 500bhp).

And, the COE system certainly reflects that time period. In a time where natural aspiration was the norm, a car's performance would generally be directly correlated to its overall displacement.

In fact, in 1990 there were a total of five passenger car categories - Cat 1 (1,000cc and below), Cat 2 (1,001cc to 1,600cc), Cat 3 (1,601cc to 2,000cc), Cat 4 (above 2,001cc), as well as Cat 7 (open category).

And, the segmentation of categories was for "social equity reasons" (as stated in the report), so the Government's intentions was clear enough - buyers shopping in the bigger capacity, more premium segments should not be competing for COEs with buyers in the more mass-market segment.

Most of the bids, expectedly, were for Cat 2. In the July 1990 tender exercise, there were about 3,600 bids for Cat 2 - reflecting not just the fact that many cars were in that particular segment, but also the strong demand for these bread-and-butter models. It is also telling (and prescient), however, that a news report noted that "the greatest over-subscription this month appeared to be for luxury cars above 2,000cc," though it should be noted that the quota for that category was just 88.

To better understand this, it's important to note the state of the automotive industry back then. In the 90s and early 2000s, many of the mass market models (chiefly from the Japanese brands) used 1.6-litre engines. These included popular cars like the Toyota Altis, Honda Civic, Mitsubishi Lancer, etc. In an era largely before widespread forced induction, premium models from the likes of the German marques had bigger displacement engines that were typically 1.8-litres and upwards (and even then, power output was still typically in the low to mid 100s for the entry-level models).

It's understandable then, for the 'cut off' mark between Cat A and B to be 1.6-litres, and 97kW. It drew a relatively obvious line between mass-market and premium models. And of course, the COE system was designed with the then market standards in mind.

Nowadays, engine displacement is certainly not directly correlated to performance. With the advent of turbocharged engines (and more recently hybrids and the like), power output has pretty much gone up across the board, even with engines getting smaller. In fact, in 2014, Ford already produced a 1.0-litre engine making 138bhp, which would have put any such car in Cat B.

As a result, the delineation between mass-market and premium models is no longer quite so clear. In fact, there are plenty of instances when models can easily straddle between the two categories depending on trim or variant.

Furthermore, with the push towards electrification, a system based around engine displacement seems even more archaic. This fails to take into account numerous relatively modern developments such as hybrids and, of course, full electric cars as well.

How to fix the COE system

Obviously, I have no policy-making jurisdiction. However, I do have some ideas as to how the COE system can be updated, not just to reflect the present realities of the automotive market, but also to better cater for changes in the future.

1. Remove the displacement cap, and raise the output cap for Cat A

|  |

Removing the displacement cap, and using output as a singular cut-off measure, would better reflect the automotive industry in 2022 and beyond. This would still be a familiar and recognisable system to most people presenting the least radical change, though it is an imperfect solution.

One notable benefit is that this would limit instances where new models launched in Singapore still get old engines (such as was the case with the Mk 7.5 Golf and the FK Civic), simply to get the car to fit into Cat A.

This would also better account for EVs, which the Government has taken baby steps towards addressing by raising the EV-specific power cap for Cat A to 110kW.

2. Peg COE Category banding to Open Market Value (OMV)

Another (perhaps better) way to peg the COE banding is against a car's OMV. A car's OMV is a much better indication of its 'worth' or 'value', rather than performance or displacement. If the idea is that luxury goods should be taxed more (as is already the case with the tiered ARF), then wouldn't it make sense to have COE tied to car value?

The LTA has previously in 2013 rejected the idea of categorising cars based on OMV, stating that it "can fluctuate significantly for different batches of the same car, due to variations in exchange rates and car model specifications. This means the same car model can end up in Cat A or Cat B at different times."

However, this hasn't stopped some other considerations to be pegged to OMV. Presently, there are already a couple of things pegged to the $20k OMV mark - the total loan percentage allowed, as well as the first ARF tier. It could follow that the OMV cut-off for Cat A be set at the same $20k OMV figure as well.

While pegging the category cut-off at $20k would still again be somewhat arbitrary, it at least allows a fairly neat way for adjusting in the future. Adjusting the OMV cut-off upwards should be done alongside the ARF tier and loan availability, which would better account for the delineation between mass-market and premium models.

3. Remove COE banding altogether

This would provide definitive incentive to push drivers towards other means of transport, such as public transport, ride-hailing and car-sharing.

And, of course, this means there's no requirement to factor in adjustments in the future, if all cars fall into a singular COE category.

Necessary change

Of course, some of the fundamental frustrations with regards to the COE system won't go away, not unless the Government wants it to. The bidding system, wholly dependent on limited supply and excess demand, brings with it fair criticisms.

Tackling issues of supply and demand is an entirely different discussion altogether. Here, we are simply looking at the mechanics of the system and whether it is ultimately still reflective of the present market reality that we find ourselves in.

Singapore has grand ambitions of being a modern, future-ready city, even in the automotive sphere. With multiple brand regional headquarters here, and even an upcoming Hyundai manufacturing facility, it would appear that those ambitions have been largely realised.

A COE system mired in the past only serves to handicap that potential progress. And it can also be to the detriment of the customer.

If distributors are having to work with their principals to fit old engines into new cars to shoehorn new cars into old categories, we as the customer are missing out on the newest and best capabilities that technological progress and advancement has to offer.

If the automotive market was still stuck with a COE system firmly lodged in the past, that would just be shooting ourselves in the foot. It's past time for change.

In 2013, then Transport Minister Lui Tuck Yew said, "This differentiation between Cat A and Cat B is certainly an improvement over what we have today, but we have to continually re-look and adjust and revise it accordingly."

Let's hope that the continued revision and adjustments actually happen. It's happened before, so it certainly can (and needs to) happen again.

In spite of how regularly we complain about the punitive financial devastation that the COE system inflicts on car buyers (especially right now), we cannot fundamentally dispute that the system works in its explicit and implicit intent - to control the overall population of cars on the road, as well as, of course, to generate plenty of revenue for the Government.

But, it is also high time to recognise that the COE system as constituted is outdated, and desperately needs to be relooked and arguably overhauled.

A relic of a past gone by

The COE mechanic was first put into effect in 1990, as part of the Vehicle Quota System. The automotive landscape was very different back then - electric cars were more concept than inevitable reality, private-hire and car-sharing were terms not even conceived, and 500bhp was considered hypercar performance (there are now modern SUVs that make more than 500bhp).

And, the COE system certainly reflects that time period. In a time where natural aspiration was the norm, a car's performance would generally be directly correlated to its overall displacement.

In fact, in 1990 there were a total of five passenger car categories - Cat 1 (1,000cc and below), Cat 2 (1,001cc to 1,600cc), Cat 3 (1,601cc to 2,000cc), Cat 4 (above 2,001cc), as well as Cat 7 (open category).

And, the segmentation of categories was for "social equity reasons" (as stated in the report), so the Government's intentions was clear enough - buyers shopping in the bigger capacity, more premium segments should not be competing for COEs with buyers in the more mass-market segment.

Most of the bids, expectedly, were for Cat 2. In the July 1990 tender exercise, there were about 3,600 bids for Cat 2 - reflecting not just the fact that many cars were in that particular segment, but also the strong demand for these bread-and-butter models. It is also telling (and prescient), however, that a news report noted that "the greatest over-subscription this month appeared to be for luxury cars above 2,000cc," though it should be noted that the quota for that category was just 88.

A look at the list of Cat A cars that got shunted into Cat B in 2013 reveals that most are from premium manufacturers It was only in 1999 that the system was refined into the one we recognise today (evidence that changes can indeed be made), with just three categories for passenger cars. And it was further in 2013 that the power cap of 97kW for Cat A was introduced. Premium models back in 2013, like the Mercedes-Benz C180 and the BMW 118i, would then fall into Cat B. This was done, again, with the explicit purpose of better delineating mass-market models from premium ones.

A look at the list of Cat A cars that got shunted into Cat B in 2013 reveals that most are from premium manufacturers It was only in 1999 that the system was refined into the one we recognise today (evidence that changes can indeed be made), with just three categories for passenger cars. And it was further in 2013 that the power cap of 97kW for Cat A was introduced. Premium models back in 2013, like the Mercedes-Benz C180 and the BMW 118i, would then fall into Cat B. This was done, again, with the explicit purpose of better delineating mass-market models from premium ones.

To better understand this, it's important to note the state of the automotive industry back then. In the 90s and early 2000s, many of the mass market models (chiefly from the Japanese brands) used 1.6-litre engines. These included popular cars like the Toyota Altis, Honda Civic, Mitsubishi Lancer, etc. In an era largely before widespread forced induction, premium models from the likes of the German marques had bigger displacement engines that were typically 1.8-litres and upwards (and even then, power output was still typically in the low to mid 100s for the entry-level models).

It's understandable then, for the 'cut off' mark between Cat A and B to be 1.6-litres, and 97kW. It drew a relatively obvious line between mass-market and premium models. And of course, the COE system was designed with the then market standards in mind.

Nowadays, engine displacement is certainly not directly correlated to performance. With the advent of turbocharged engines (and more recently hybrids and the like), power output has pretty much gone up across the board, even with engines getting smaller. In fact, in 2014, Ford already produced a 1.0-litre engine making 138bhp, which would have put any such car in Cat B.

As a result, the delineation between mass-market and premium models is no longer quite so clear. In fact, there are plenty of instances when models can easily straddle between the two categories depending on trim or variant.

Furthermore, with the push towards electrification, a system based around engine displacement seems even more archaic. This fails to take into account numerous relatively modern developments such as hybrids and, of course, full electric cars as well.

How to fix the COE system

Obviously, I have no policy-making jurisdiction. However, I do have some ideas as to how the COE system can be updated, not just to reflect the present realities of the automotive market, but also to better cater for changes in the future.

1. Remove the displacement cap, and raise the output cap for Cat A

Removing the displacement cap, and using output as a singular cut-off measure, would better reflect the automotive industry in 2022 and beyond. This would still be a familiar and recognisable system to most people presenting the least radical change, though it is an imperfect solution.

The Mk 7.5 Golf was offered locally with an older 1.4-litre engine, rather than the new 1.5-litre engine being debuted Where do we draw the cut-off? Any figure would still be somewhat arbitrary (but isn't the current system also relatively arbitrary?), but one reference point can be the 110kW cap that has already been implemented for EVs.

The Mk 7.5 Golf was offered locally with an older 1.4-litre engine, rather than the new 1.5-litre engine being debuted Where do we draw the cut-off? Any figure would still be somewhat arbitrary (but isn't the current system also relatively arbitrary?), but one reference point can be the 110kW cap that has already been implemented for EVs.

One notable benefit is that this would limit instances where new models launched in Singapore still get old engines (such as was the case with the Mk 7.5 Golf and the FK Civic), simply to get the car to fit into Cat A.

This would also better account for EVs, which the Government has taken baby steps towards addressing by raising the EV-specific power cap for Cat A to 110kW.

2. Peg COE Category banding to Open Market Value (OMV)

Another (perhaps better) way to peg the COE banding is against a car's OMV. A car's OMV is a much better indication of its 'worth' or 'value', rather than performance or displacement. If the idea is that luxury goods should be taxed more (as is already the case with the tiered ARF), then wouldn't it make sense to have COE tied to car value?

The LTA has previously in 2013 rejected the idea of categorising cars based on OMV, stating that it "can fluctuate significantly for different batches of the same car, due to variations in exchange rates and car model specifications. This means the same car model can end up in Cat A or Cat B at different times."

However, this hasn't stopped some other considerations to be pegged to OMV. Presently, there are already a couple of things pegged to the $20k OMV mark - the total loan percentage allowed, as well as the first ARF tier. It could follow that the OMV cut-off for Cat A be set at the same $20k OMV figure as well.

While pegging the category cut-off at $20k would still again be somewhat arbitrary, it at least allows a fairly neat way for adjusting in the future. Adjusting the OMV cut-off upwards should be done alongside the ARF tier and loan availability, which would better account for the delineation between mass-market and premium models.

3. Remove COE banding altogether

If a car-lite future is truly on the cards, then perhaps all cars should be treated (and taxed) equally If cars are simply a luxury good altogether, and the Government is sincere about pushing towards a car-lite future, then perhaps COE banding should be removed altogether. Every car is treated the same - as a luxury good, with the respective taxation that comes with it.

If a car-lite future is truly on the cards, then perhaps all cars should be treated (and taxed) equally If cars are simply a luxury good altogether, and the Government is sincere about pushing towards a car-lite future, then perhaps COE banding should be removed altogether. Every car is treated the same - as a luxury good, with the respective taxation that comes with it.

This would provide definitive incentive to push drivers towards other means of transport, such as public transport, ride-hailing and car-sharing.

And, of course, this means there's no requirement to factor in adjustments in the future, if all cars fall into a singular COE category.

Necessary change

Of course, some of the fundamental frustrations with regards to the COE system won't go away, not unless the Government wants it to. The bidding system, wholly dependent on limited supply and excess demand, brings with it fair criticisms.

Tackling issues of supply and demand is an entirely different discussion altogether. Here, we are simply looking at the mechanics of the system and whether it is ultimately still reflective of the present market reality that we find ourselves in.

Singapore has grand ambitions of being a modern, future-ready city, even in the automotive sphere. With multiple brand regional headquarters here, and even an upcoming Hyundai manufacturing facility, it would appear that those ambitions have been largely realised.

A COE system mired in the past only serves to handicap that potential progress. And it can also be to the detriment of the customer.

If distributors are having to work with their principals to fit old engines into new cars to shoehorn new cars into old categories, we as the customer are missing out on the newest and best capabilities that technological progress and advancement has to offer.

If the automotive market was still stuck with a COE system firmly lodged in the past, that would just be shooting ourselves in the foot. It's past time for change.

In 2013, then Transport Minister Lui Tuck Yew said, "This differentiation between Cat A and Cat B is certainly an improvement over what we have today, but we have to continually re-look and adjust and revise it accordingly."

Let's hope that the continued revision and adjustments actually happen. It's happened before, so it certainly can (and needs to) happen again.

But, it is also high time to recognise that the COE system as constituted is outdated, and desperately needs to be relooked and arguably overhauled.

A relic of a past gone by

The COE mechanic was first put into effect in 1990, as part of the Vehicle Quota System. The automotive landscape was very different back then - electric cars were more concept than inevitable reality, private-hire and car-sharing were terms not even conceived, and 500bhp was considered hypercar performance (there are now modern SUVs that make more than 500bhp).

And, the COE system certainly reflects that time period. In a time where natural aspiration was the norm, a car's performance would generally be directly correlated to its overall displacement.

In fact, in 1990 there were a total of five passenger car categories - Cat 1 (1,000cc and below), Cat 2 (1,001cc to 1,600cc), Cat 3 (1,601cc to 2,000cc), Cat 4 (above 2,001cc), as well as Cat 7 (open category).

And, the segmentation of categories was for "social equity reasons" (as stated in the report), so the Government's intentions was clear enough - buyers shopping in the bigger capacity, more premium segments should not be competing for COEs with buyers in the more mass-market segment.

Most of the bids, expectedly, were for Cat 2. In the July 1990 tender exercise, there were about 3,600 bids for Cat 2 - reflecting not just the fact that many cars were in that particular segment, but also the strong demand for these bread-and-butter models. It is also telling (and prescient), however, that a news report noted that "the greatest over-subscription this month appeared to be for luxury cars above 2,000cc," though it should be noted that the quota for that category was just 88.

To better understand this, it's important to note the state of the automotive industry back then. In the 90s and early 2000s, many of the mass market models (chiefly from the Japanese brands) used 1.6-litre engines. These included popular cars like the Toyota Altis, Honda Civic, Mitsubishi Lancer, etc. In an era largely before widespread forced induction, premium models from the likes of the German marques had bigger displacement engines that were typically 1.8-litres and upwards (and even then, power output was still typically in the low to mid 100s for the entry-level models).

It's understandable then, for the 'cut off' mark between Cat A and B to be 1.6-litres, and 97kW. It drew a relatively obvious line between mass-market and premium models. And of course, the COE system was designed with the then market standards in mind.

Nowadays, engine displacement is certainly not directly correlated to performance. With the advent of turbocharged engines (and more recently hybrids and the like), power output has pretty much gone up across the board, even with engines getting smaller. In fact, in 2014, Ford already produced a 1.0-litre engine making 138bhp, which would have put any such car in Cat B.

As a result, the delineation between mass-market and premium models is no longer quite so clear. In fact, there are plenty of instances when models can easily straddle between the two categories depending on trim or variant.

Furthermore, with the push towards electrification, a system based around engine displacement seems even more archaic. This fails to take into account numerous relatively modern developments such as hybrids and, of course, full electric cars as well.

How to fix the COE system

Obviously, I have no policy-making jurisdiction. However, I do have some ideas as to how the COE system can be updated, not just to reflect the present realities of the automotive market, but also to better cater for changes in the future.

1. Remove the displacement cap, and raise the output cap for Cat A

The Forester's 2.0-litre engine (left) produces comparable power to the Ateca's 1.4-litre lump, proof that displacement isn't everything

As cars get more technologically advanced and engine technology becomes increasingly efficient, manufacturers can get more performance out of their motors. As a consequence, displacement is no longer a good measure of performance. With turbocharging, most engines are getting smaller while output generally gets higher. Removing the displacement cap, and using output as a singular cut-off measure, would better reflect the automotive industry in 2022 and beyond. This would still be a familiar and recognisable system to most people presenting the least radical change, though it is an imperfect solution.

One notable benefit is that this would limit instances where new models launched in Singapore still get old engines (such as was the case with the Mk 7.5 Golf and the FK Civic), simply to get the car to fit into Cat A.

This would also better account for EVs, which the Government has taken baby steps towards addressing by raising the EV-specific power cap for Cat A to 110kW.

2. Peg COE Category banding to Open Market Value (OMV)

Another (perhaps better) way to peg the COE banding is against a car's OMV. A car's OMV is a much better indication of its 'worth' or 'value', rather than performance or displacement. If the idea is that luxury goods should be taxed more (as is already the case with the tiered ARF), then wouldn't it make sense to have COE tied to car value?

The LTA has previously in 2013 rejected the idea of categorising cars based on OMV, stating that it "can fluctuate significantly for different batches of the same car, due to variations in exchange rates and car model specifications. This means the same car model can end up in Cat A or Cat B at different times."

However, this hasn't stopped some other considerations to be pegged to OMV. Presently, there are already a couple of things pegged to the $20k OMV mark - the total loan percentage allowed, as well as the first ARF tier. It could follow that the OMV cut-off for Cat A be set at the same $20k OMV figure as well.

While pegging the category cut-off at $20k would still again be somewhat arbitrary, it at least allows a fairly neat way for adjusting in the future. Adjusting the OMV cut-off upwards should be done alongside the ARF tier and loan availability, which would better account for the delineation between mass-market and premium models.

3. Remove COE banding altogether

This would provide definitive incentive to push drivers towards other means of transport, such as public transport, ride-hailing and car-sharing.

And, of course, this means there's no requirement to factor in adjustments in the future, if all cars fall into a singular COE category.

Necessary change

Of course, some of the fundamental frustrations with regards to the COE system won't go away, not unless the Government wants it to. The bidding system, wholly dependent on limited supply and excess demand, brings with it fair criticisms.

Tackling issues of supply and demand is an entirely different discussion altogether. Here, we are simply looking at the mechanics of the system and whether it is ultimately still reflective of the present market reality that we find ourselves in.

Singapore has grand ambitions of being a modern, future-ready city, even in the automotive sphere. With multiple brand regional headquarters here, and even an upcoming Hyundai manufacturing facility, it would appear that those ambitions have been largely realised.

A COE system mired in the past only serves to handicap that potential progress. And it can also be to the detriment of the customer.

If distributors are having to work with their principals to fit old engines into new cars to shoehorn new cars into old categories, we as the customer are missing out on the newest and best capabilities that technological progress and advancement has to offer.

If the automotive market was still stuck with a COE system firmly lodged in the past, that would just be shooting ourselves in the foot. It's past time for change.

In 2013, then Transport Minister Lui Tuck Yew said, "This differentiation between Cat A and Cat B is certainly an improvement over what we have today, but we have to continually re-look and adjust and revise it accordingly."

Let's hope that the continued revision and adjustments actually happen. It's happened before, so it certainly can (and needs to) happen again.

Thank You For Your Subscription.