'Carbon neutrality': More than just making electric cars?

07 Nov 2023|2,304 views

The lack of urgency with which Toyota appears to be churning out EVs may seem puzzling at first glance - especially since its closest competitors have been considerably quicker (and more aggressive) in putting fully-electric models onto the market.

But dig gingerly into the strategy it's outlined for the future, and you'll find the same two words its competitors have been trumpeting also lodged at the heart of its 'Multi-Pathway Approach': Carbon neutrality. In fact, alongside the idea of 'sustainability', these are probably the most frequently-heard buzzwords today.

Avoiding these terms in 2023 is impossible, and it's not just about cars too. Everywhere we look, companies and brands from clothing manufacturers to coffee producers are finding means of becoming more sustainable - in materials, in processes, and of course, in the final products they end up making.

Within the automotive industry, however, the concept of sustainability has very much been intertwined with the idea of electric power. And this connection - which we've perhaps grown to take as the unquestionable, gospel truth - is perhaps worth pondering a bit more about.

Refresher! Zero-emission cars are not 'zero-emissions' to produce

Before proceeding further, it'd be ironic to fling the term 'carbon neutrality' around so flippantly without first setting clear parameters for what it means. To go carbon neutral can be most simply understood as removing as much carbon from the atmosphere as is initially emitted.

Or best of all, to not emit anything to begin with.

The idea of electric cars being emission-free is technically not wrong, but it's also only true to a certain degree. Here, it's helpful to recall the idea of 'lifecycle emissions' - which encompass everything that is emitted even before a car is assembled at the factory, to the point that it eventually finds itself in a scrapyard.

On the one hand, carmakers are rapidly switching over to facilities that run either entirely or mostly on renewable energy; powered either by solar panels, or wind turbines. They are also slowly working towards closed-loop recycling. (Just imagine if every single component from your Corolla Altis could go to a special facility where it was broken down, then given a new lease of life within the next-gen car.)

On the other hand, however, that doesn't change the fact that the initial phase of the 'lifecycle' - the manufacturing process - has certainly not reached the 'zero-emissions' point yet. While carmakers are rapidly switching to facilities that run either entirely or mostly on renewable energy, building a car (unsurprisingly) still requires lots of energy and resources - whether it's the vegan leather wrapping the seats of your new 5 Series, the glass covering the EQS SUV's Hyperscreen, or of course, the lithium-ion battery of the Toyota bZ4X.

They're not entirely 'zero-emissions' to run either

On the other end of the 'lifecycle', there's also one final important factor to consider: The fact that the production of electricity is still not completely powered by renewable sources in most parts of the world.

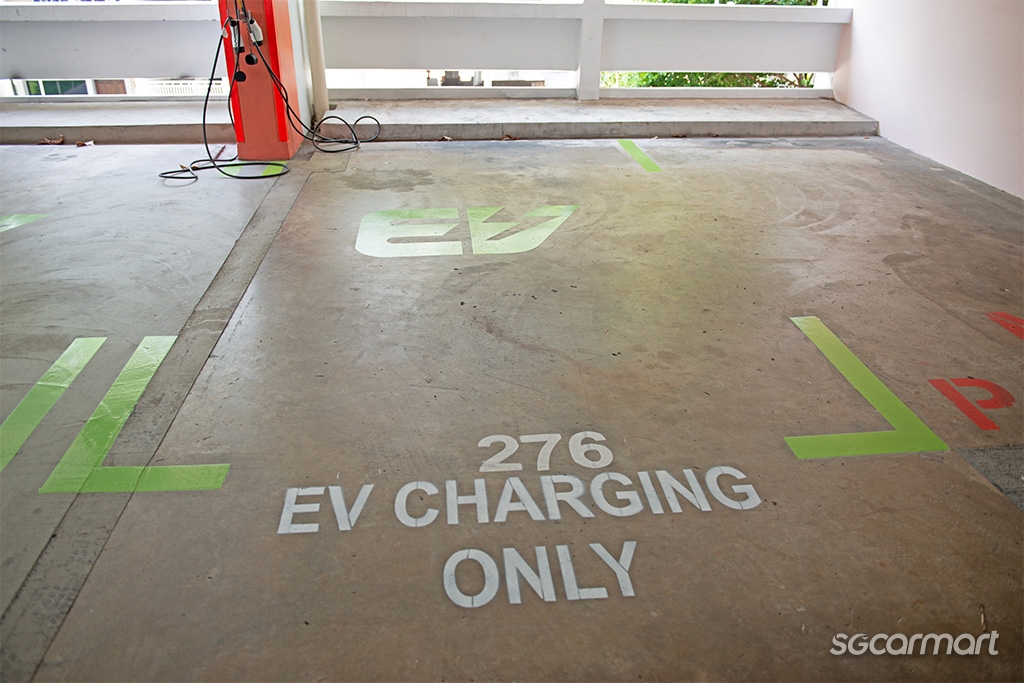

Singapore is a great example of this; electricity is still generated largely by natural gas on our shores. In other words, even if your EV itself is not emitting any carbon as it silently rolls down Orchard Road, some level of emissions has already occurred in the process of generating that electricity that goes into its battery at every charging point.

Here, it's worth noting that even when considering both the resources exhausted in the manufacturing process and also the carbon emitted during electricity-generation, EVs have been proven time and again to be better for the environment than their combustion-powered counterparts.

Nonetheless, the fact also remains that even in the scenario that every car right now is converted to an EV, carbon neutrality - as defined above - will still not be achieved in the automotive space.

On the note of making every car an EV…

Global vs local impact: Towards the most sensible solution, in the quickest manner

Here's where another big catch lies: Not every country - and perhaps more specifically, not every area within a country - can go fully electric as quickly as desired.

Singaporeans throw the term "range anxiety" around rather often but objectively speaking, our physical environment actually serves as the perfect textbook example for where EVs can take flight. Point-to-point journeys are short, resources to ramp up charging stations are steadily multiplying, and just as importantly, our power grid infrastructure is stable.

Admittedly, even a 20-minute "fast charge" at Millenia Walk far exceeds a three-minute quick pump at Shell - but this is more an inevitable matter of learning to adapt to a new way of living (imagine the more serious issue of lacking charging infrastructure altogether).

Not every other country has this benefit.

Think Australia, or the U.S.A, where eight-hour drives spanning a few hundred kilometres are unquestioned and routine experiences for those making inter-state trips, either for weekend getaways or family visits. Undeniably, the use case for EVs remains much stronger within the boundaries of a city as opposed to the context of regular cross-country treks.

In other words, markets are rarely one and the same when it comes to reducing emissions. Accordingly, blanket solutions (read: going fully electric) are ultimately ineffective. After all, the reduction of the transport sector's carbon footprint should not be contingent on electric cars alone; all cars (and vehicles) need to emit as little as possible - and as soon as possible.

What happens, then, to those for whom an EV really makes less sense right now?

Instead of viewing the transport sector as an all-or-nothing switch from "non-electric" to "fully-electric", the heart of the matter should instead revolve around the question of "What do cleaner cars look like, and how can we work towards a scenario where we have more of them on our roads?"

(That's also already discounting the fact that significant price gaps still exist between even entry-level EVs and ICE cars - a situation that is more pronounced in countries that do not incentivise EV-ownership.)

A genuinely zero-emissions landscape remains a goal we'll always be working towards in the future - but in the meantime, the focus must still return to lowering emissions in the present. Interestingly, our own government seems to be taking this tack for Singapore: The Singapore Green Plan 2030 (just seven years from now!) states that all new cars registered by then will have to be "cleaner-energy models" - but not necessarily fully-electric.

Differentiated approaches for a complex goal

If everything thus far has sounded very messy and confusing, the tough and unavoidable truth is indeed that the concept of carbon neutrality is extremely nuanced; difficult to dissect based on the reductive, singular question of whether a car is fully electric or not.

You could be driving an electric car, but its emission-reducing potential would not be maximised if the electricity used to power it wasn't sustainably produced to begin with. Likewise, the manufacture of the car itself could be powered by 'green' energy, but its batteries rely on rare earths and metals, for which any mining invariably causes some level of environmental degradation.

Worst of all, an electric car could possibly not even make sense to you now - or in the next five years.

The response to that, then? That there is truly no strategy that can be labelled as 100% correct or effective on the path to decarbonisation - at least not yet.

Unsurprisingly, our largest carmakers know this. And while overlaps between strategies exist - the involvement of electric cars being one of the main pillars - this complexity is exactly why each brand has a slightly varying take on how they intend to decarbonise.

BMW's fifth-generation eDrive motors - whose designs have negated the need for rare earth minerals - are a good example for tackling things upstream on the supply chain front. EV batteries are still resource-intensive, but cutting this one component out has undeniably also reduced the need for mining. On a different note of maximising the emission-free nature of EVs, Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen, have built their own charging networks in Europe with a commitment to ensuring that these supply only electricity produced by renewable sources.

Conversely, of course, we then also have blueprints that do not rely on a full-EV portfolio, and still see combustion power as part of the puzzle. Porsche and Mazda - two very different brands - have both voiced hope in a future where carbon-neutral fuel (or e-Fuels) become viable lifelines for the combustion engine.

And one could certainly remain sceptical of the glacial pace at which Toyota seems to be pushing out BEVs. But on the flip side, it's also worth giving the company's argument some time of day: That pushing out hybrid cars in every segment first may actually be more effective in reducing emissions, even as it invests heavily into fuel cell electric vehicles that run on hydrogen.

Beyond the buzzwords

To be crystal clear once more, fully-electric cars - and fully-electric brands (as we've seen from BYD and Tesla) are of paramount importance in helping to 'clean up' the transport sector.

Yet without knocking them down, caution should still be exercised in thinking of them as silver bullets to alleviating the effects of climate change.

BYD and Tesla are two particularly interesting names to note since they're fully-electric and have made clear attempts to integrate renewable energy into their production processes on the one hand… yet also have less concretely defined goals in reaching carbon neutrality among today's carmakers (at least at the time of writing).

After all, the topic of carbon neutrality is a multi-faceted and vastly complex issue - one that doesn't just start and end with what comes out of the tailpipes of the vehicles plying our roads. The next time a brand invites you into their 'zero-emissions' world, it's worth wondering exactly where the lines of computation lie.

Here are a few other stories that may interest you!

EVs boast zero tailpipe-emissions, but how is the electricity that powers them generated?

The lack of urgency with which Toyota appears to be churning out EVs may seem puzzling at first glance - especially since its closest competitors have been considerably quicker (and more aggressive) in putting fully-electric models onto the market.

But dig gingerly into the strategy it's outlined for the future, and you'll find the same two words its competitors have been trumpeting also lodged at the heart of its 'Multi-Pathway Approach': Carbon neutrality. In fact, alongside the idea of 'sustainability', these are probably the most frequently-heard buzzwords today.

Avoiding these terms in 2023 is impossible, and it's not just about cars too. Everywhere we look, companies and brands from clothing manufacturers to coffee producers are finding means of becoming more sustainable - in materials, in processes, and of course, in the final products they end up making.

Within the automotive industry, however, the concept of sustainability has very much been intertwined with the idea of electric power. And this connection - which we've perhaps grown to take as the unquestionable, gospel truth - is perhaps worth pondering a bit more about.

Refresher! Zero-emission cars are not 'zero-emissions' to produce

Before proceeding further, it'd be ironic to fling the term 'carbon neutrality' around so flippantly without first setting clear parameters for what it means. To go carbon neutral can be most simply understood as removing as much carbon from the atmosphere as is initially emitted.

Or best of all, to not emit anything to begin with.

The idea of electric cars being emission-free is technically not wrong, but it's also only true to a certain degree. Here, it's helpful to recall the idea of 'lifecycle emissions' - which encompass everything that is emitted even before a car is assembled at the factory, to the point that it eventually finds itself in a scrapyard.

On the one hand, carmakers are rapidly switching over to facilities that run either entirely or mostly on renewable energy; powered either by solar panels, or wind turbines. They are also slowly working towards closed-loop recycling. (Just imagine if every single component from your Corolla Altis could go to a special facility where it was broken down, then given a new lease of life within the next-gen car.)

On the other hand, however, that doesn't change the fact that the initial phase of the 'lifecycle' - the manufacturing process - has certainly not reached the 'zero-emissions' point yet. While carmakers are rapidly switching to facilities that run either entirely or mostly on renewable energy, building a car (unsurprisingly) still requires lots of energy and resources - whether it's the vegan leather wrapping the seats of your new 5 Series, the glass covering the EQS SUV's Hyperscreen, or of course, the lithium-ion battery of the Toyota bZ4X.

They're not entirely 'zero-emissions' to run either

On the other end of the 'lifecycle', there's also one final important factor to consider: The fact that the production of electricity is still not completely powered by renewable sources in most parts of the world.

Singapore is a great example of this; electricity is still generated largely by natural gas on our shores. In other words, even if your EV itself is not emitting any carbon as it silently rolls down Orchard Road, some level of emissions has already occurred in the process of generating that electricity that goes into its battery at every charging point.

Here, it's worth noting that even when considering both the resources exhausted in the manufacturing process and also the carbon emitted during electricity-generation, EVs have been proven time and again to be better for the environment than their combustion-powered counterparts.

Nonetheless, the fact also remains that even in the scenario that every car right now is converted to an EV, carbon neutrality - as defined above - will still not be achieved in the automotive space.

On the note of making every car an EV…

Global vs local impact: Towards the most sensible solution, in the quickest manner

Here's where another big catch lies: Not every country - and perhaps more specifically, not every area within a country - can go fully electric as quickly as desired.

Singaporeans throw the term "range anxiety" around rather often but objectively speaking, our physical environment actually serves as the perfect textbook example for where EVs can take flight. Point-to-point journeys are short, resources to ramp up charging stations are steadily multiplying, and just as importantly, our power grid infrastructure is stable.

Admittedly, even a 20-minute "fast charge" at Millenia Walk far exceeds a three-minute quick pump at Shell - but this is more an inevitable matter of learning to adapt to a new way of living (imagine the more serious issue of lacking charging infrastructure altogether).

Not every other country has this benefit.

Think Australia, or the U.S.A, where eight-hour drives spanning a few hundred kilometres are unquestioned and routine experiences for those making inter-state trips, either for weekend getaways or family visits. Undeniably, the use case for EVs remains much stronger within the boundaries of a city as opposed to the context of regular cross-country treks.

In other words, markets are rarely one and the same when it comes to reducing emissions. Accordingly, blanket solutions (read: going fully electric) are ultimately ineffective. After all, the reduction of the transport sector's carbon footprint should not be contingent on electric cars alone; all cars (and vehicles) need to emit as little as possible - and as soon as possible.

What happens, then, to those for whom an EV really makes less sense right now?

Instead of viewing the transport sector as an all-or-nothing switch from "non-electric" to "fully-electric", the heart of the matter should instead revolve around the question of "What do cleaner cars look like, and how can we work towards a scenario where we have more of them on our roads?"

(That's also already discounting the fact that significant price gaps still exist between even entry-level EVs and ICE cars - a situation that is more pronounced in countries that do not incentivise EV-ownership.)

A genuinely zero-emissions landscape remains a goal we'll always be working towards in the future - but in the meantime, the focus must still return to lowering emissions in the present. Interestingly, our own government seems to be taking this tack for Singapore: The Singapore Green Plan 2030 (just seven years from now!) states that all new cars registered by then will have to be "cleaner-energy models" - but not necessarily fully-electric.

Differentiated approaches for a complex goal

If everything thus far has sounded very messy and confusing, the tough and unavoidable truth is indeed that the concept of carbon neutrality is extremely nuanced; difficult to dissect based on the reductive, singular question of whether a car is fully electric or not.

You could be driving an electric car, but its emission-reducing potential would not be maximised if the electricity used to power it wasn't sustainably produced to begin with. Likewise, the manufacture of the car itself could be powered by 'green' energy, but its batteries rely on rare earths and metals, for which any mining invariably causes some level of environmental degradation.

Worst of all, an electric car could possibly not even make sense to you now - or in the next five years.

The response to that, then? That there is truly no strategy that can be labelled as 100% correct or effective on the path to decarbonisation - at least not yet.

Unsurprisingly, our largest carmakers know this. And while overlaps between strategies exist - the involvement of electric cars being one of the main pillars - this complexity is exactly why each brand has a slightly varying take on how they intend to decarbonise.

BMW's fifth-generation eDrive motors - whose designs have negated the need for rare earth minerals - are a good example for tackling things upstream on the supply chain front. EV batteries are still resource-intensive, but cutting this one component out has undeniably also reduced the need for mining. On a different note of maximising the emission-free nature of EVs, Mercedes-Benz and Volkswagen, have built their own charging networks in Europe with a commitment to ensuring that these supply only electricity produced by renewable sources.

Conversely, of course, we then also have blueprints that do not rely on a full-EV portfolio, and still see combustion power as part of the puzzle. Porsche and Mazda - two very different brands - have both voiced hope in a future where carbon-neutral fuel (or e-Fuels) become viable lifelines for the combustion engine.

And one could certainly remain sceptical of the glacial pace at which Toyota seems to be pushing out BEVs. But on the flip side, it's also worth giving the company's argument some time of day: That pushing out hybrid cars in every segment first may actually be more effective in reducing emissions, even as it invests heavily into fuel cell electric vehicles that run on hydrogen.

Beyond the buzzwords

To be crystal clear once more, fully-electric cars - and fully-electric brands (as we've seen from BYD and Tesla) are of paramount importance in helping to 'clean up' the transport sector.

Yet without knocking them down, caution should still be exercised in thinking of them as silver bullets to alleviating the effects of climate change.

BYD and Tesla are two particularly interesting names to note since they're fully-electric and have made clear attempts to integrate renewable energy into their production processes on the one hand… yet also have less concretely defined goals in reaching carbon neutrality among today's carmakers (at least at the time of writing).

After all, the topic of carbon neutrality is a multi-faceted and vastly complex issue - one that doesn't just start and end with what comes out of the tailpipes of the vehicles plying our roads. The next time a brand invites you into their 'zero-emissions' world, it's worth wondering exactly where the lines of computation lie.

Here are a few other stories that may interest you!

EVs boast zero tailpipe-emissions, but how is the electricity that powers them generated?

Thank You For Your Subscription.